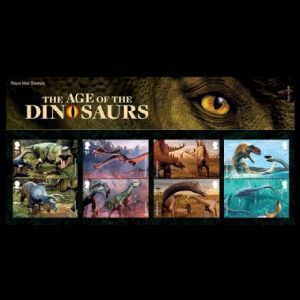

UK 2024 "The Age of the Dinosaurs" (Part I - Prehistoric Animals)

| <prev | back to index | next> |

| Issue Date | 12.03.2024 |

| ID | Michel: 5383-5390; Scott: Stanley Gibbons: Yvert: Category: pR |

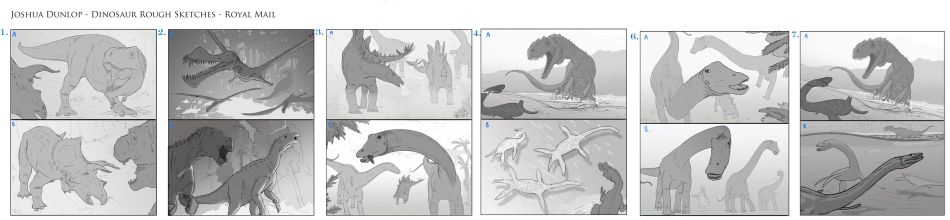

| Design | Artwork: Joshua Dunlop; Stamps design: "The Chase" creative consultants. |

| Stamps in set | 8 |

| Value |

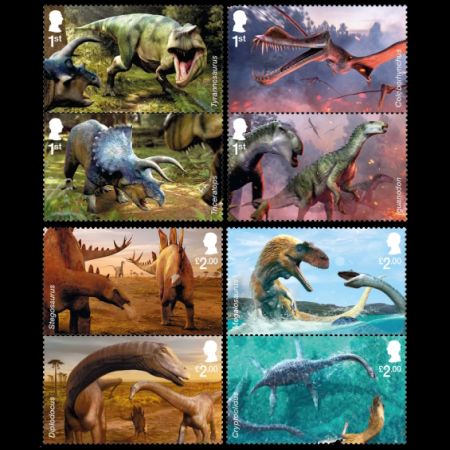

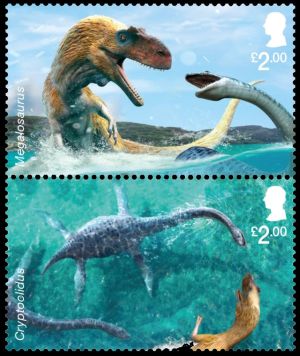

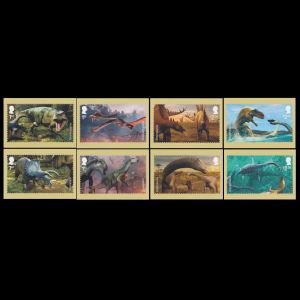

First Class - Tyrannosaurus First Class - Triceratops First Class - Coloborhynchus First Class - Iguanodon GBP 2 - Stegosaurus GBP 2 - Diplodocus GBP 2 - Megalosaurus GBP 2 - Cryptoclidus * First Class rate was equivalent to GBP 1,25 at the time of the stamps issue. * GBP 2 is the international economy rate for letters up to 100 grams. |

| Emission/Type | commemorative |

| Issue place | London, Lyme Regis |

| Size (width x height) | 50mm x 30mm |

| Layout | 4 stamps-sheets of 60 with 15 vertical se-tenant pairs |

| Products | FDC x2, PP x1, Coins x2, Coin FDC x2 |

| Paper | Phoshor bars as appropriate, with PVA gum |

| Perforation | 14x14 |

| Print Technique | Lithography |

| Printed by | Cartor Security Printers |

| Quantity | |

| Issuing Authority | Royal Mail |

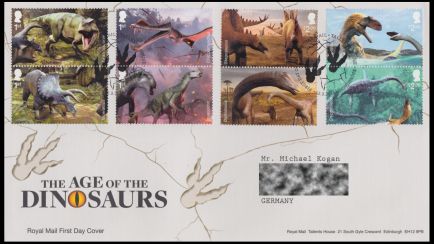

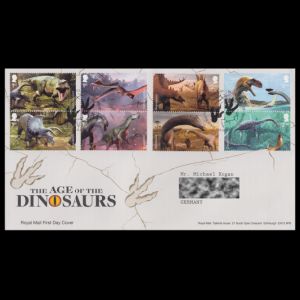

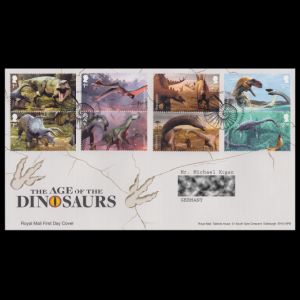

On March 12th, 2024, the Royal Mail issued the set "The Age of the Dinosaurs". The pre-sale of these stamps started one week ahead of the official release, on March 5th, 2024, to allow national and international collectors to prepare their covers for cancellations by the First-Day-of-Issue Postmarks.

According to the Royal Mail rules,

prepared covers or postcards of the national customers must be sent to

the relevant Handstamp Centre by the date of the required Handstamp.

Overseas customers may submit covers, to the relevant Handstamp Centre,

within 28 days of the date of the postmark required.

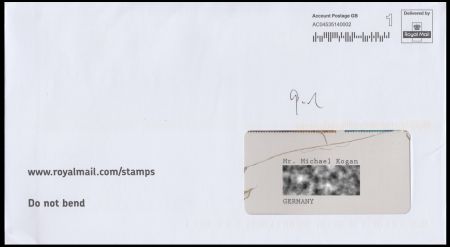

During the pre-sale week, it was possible to order addressed FDCs with an address printed by the Royal Mail on the bottom-right side of these covers. This service was not available after March 12th, 2024 (the issue date of the set).

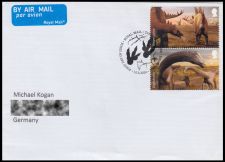

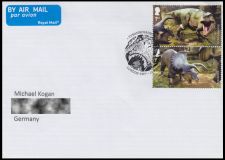

To prevent damage, the Royal Mail posted addressed FDCs in another envelope (see below). On the other hand, the tracks of the mail sorting machine were left on the envelope, rather FDC - pity, as it could be a good indication the FDC has gone through the post. Otherwise, some people (even a jury) might say the FDC never went through the post and the address was just printed on.

|

|

| FDC with prehistoric animals stamps of Great Britain 2024, posted to Germany | Addressed FDC with prehistoric animals stamps of Great Britain 2024 |

The set "The Age of the Dinosaurs" includes four pairs of stamps with reconstructions of prehistoric animals (every pair of the stamps shows an interaction of animals of two species) and the Mini-Sheet with four self-adhesive stamps shows Mary Anning and three of the fossils she unearthed along the Dorset coastline.

Due to the fact they looks differently both thematically and artistically, their description was split by two articles.

- This article is about the stamps set of the four pairs with reconstructions of prehistoric animals.

- The article about Mary Anning and her fossils is here.

The "The Age of the Dinosaurs" set has been carefully created in partnership with the Natural History Museum, using scientists from no less than six different specializations of palaeontology. The set was issued by the Royal Mail to celebrate the 200th anniversary of description of the first dinosaur. When clergyman and palaeontologist William Buckland named his findings of the fossilised remains of a prehistoric creature "Megalosaurus" (meaning "great lizard") in 1824, this was the first scientific description of what became known as a dinosaur. The new designs by digital illustrator Joshua Dunlop combine scientific accuracy with artistic brilliance in a captivating homage to the wonders of palaeontology, appealing to both stamp enthusiasts and dinosaur fans alike.

David Gold, Director of External Affairs and Policy of the Royal Mail said: We were thrilled to feature incredible dinosaurs from the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex to graceful Diplodocus as well as other fascinating prehistoric reptiles in their natural habitats. It is fitting [the issue of the stamps set] in the week of International Women’s Day that we pay tribute to Mary Anning with four images of some of the fossils she discovered. She was one of the greatest fossil hunters of the 19th century, making a major contribution to our understanding of the majestic creatures that roamed the Earth hundreds of millions of years ago. |

Maxine Lister, Head of Licensing at the Natural History Museum, said:We were thrilled when Royal Mail approached us to collaborate on these brilliant sets of stamps. It’s perfect timing too, as we have just celebrated the 200th anniversary since the naming of the first dinosaur, the Megalosaurus, which features as part of this collection. Our mission is to create advocates for the planet and we hope these stunning designs inspire everyone to discover a bit more about our natural world, whether that be the creatures that lived here before us, or the pioneering figures who shaped our understanding of them today. |

The artist, Joshua Dunlop said:I am incredibly proud to finally announce that I created the artwork for Royal Mail's brand new stamp collection 'Age of the Dinosaurs' in conjunction with Natural History Museum, London. These were approved by the King himself! |

The design of these stamps were created by “The Chase” creative consultants agency based on the artwork of Joshua Dunlop. "The Chase" wanted to avoid the usual cliched imagery of dinosaurs standing in a tropical scene roaring in front of an exploding volcano. They wanted to explore an approach more akin to that of award-winning wildlife photography. They wanted the images to look as real as possible with different landscapes, in different weather conditions and at different times of the day.

The stamps were printed in se-tenant pairs. However, rather than have two unconnected images "The Chase" used the format to their advantage by placing both prehistoric animals in the same scene (after checking with experts at the Natural History Museum that this would have been able to happen), but from completely opposite angles, almost as if the moment was captured by two photographers from different reference points at exactly the same time.

About the artist:

|

Mr. Joshua Dunlop is a freelance professional Concept artist, from Exeter in the UK, who studied art at the University of West London and Teesside University between 2008 and 2015. Joshua specialises in creatures for companies such as Disney and Netflix as well as illustrations for promotional material like the stamps.

Concept artist refers to artist that develops ideas and concepts through artwork for a variety of elements of a project. For example, if the artist were working on a film that had a Tyrannosaurus in it, he would do loads of different sketches and designs to show a director, who would pick which elements he like and the artist would work up a final design that would be passed on to the visual effects team which would eventually end up in the film.

The stamp sketches and final images, created by Joshua Dunlop for the Royal Mail. Images credit: Art Station of Joshua Dunlop.

Joshua Dunlop explained about his work on these stamps:

Those Dinosaurs are incredible, but when designing them I wanted to give them all my own style while keeping up with the most up to date understanding of Dinosaur anatomy. Thankfully I had incredible palaeontologists and palaeobotanists at the Natural History Museum in London to guide me on everything. They also gave me artwork from previous dinosaur projects they had run for guidance on the colours etc.

The "The Age of the Dinosaurs" were the first stamps designed by Mr. Dunlop for the Royal Mail, who found his work on Artstation website and reached out to him. Joshua doesn't have any video or photo shows his work about the Dinosaur stamps as they are specifically the property of Royal Mail and he didn't film anything through the process, but his other videos show how he generally put his pictures together: "Tyrantrum Time Lapse" (11 minutes YouTube video).

The Mesozoic Era, or the "Age of the Dinosaurs" as it is commonly known, lasted from 252 to 66 million years ago and comprises, in order from oldest to youngest, the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.

|

| Mary Anning on the Age of the Dinosaurs stamp of Great Britain 2024, MiNr.: 5391, Scott: |

Fossilised remains help paleontologists to unearth the secrets of these incredible creatures, and one of the greatest fossil hunters of the 19th century was Mary Anning.

Mary Anning lived during a time when it was fashionable for wealthy Georgians to visit seaside towns to acquire fossils to add to their cabinets of curiosities.

It was also when paleontology was becoming recognised as a branch of the natural sciences. Anning spent her life unearthing "curios" from the fossil-rich cliffs near her home in Lyme Regis, Dorset, to sell to tourists and scientific collectors alike, and made many important discoveries.

A fascination with prehistoric life continues today. paleontologists study all fossilised past life, including corals, fishes, mammals and plants, in addition to prehistoric reptiles. Fossils can help us not only to learn about the lives of these species, but to understand what the Earth was like in the past. From the mighty Tyrannosaurus Rex of the Late Cretaceous to the graceful Diplodocus of the Jurassic, each of the eight stamps transports collectors to a specific era, capturing the essence of these fascinating prehistoric creatures in their habitats.

The following prehistoric animals were depicted in their mighty habitats on the stamps

Four "British" prehistoric animals: the pterosaur Coloborhynchus, the plesiosaur Cryptoclidus and two dinosaurs: Iguanodon and Megalosaurus.

Fossils of all eight prehistoric animals depicted on these stamps are on display in the Natural History Museum in London.

The Natural History Museum in London on the cover of booklet with inland stamps of UK 1981.

The Natural History Museum in London, established in 1881, is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. The museum is home to life and earth science specimens comprising some 80 million items within five main collections: botany, entomology, mineralogy, palaeontology, and zoology. Only a fraction of them are on display. Given the age of the institution, many of the collections have great historical as well as scientific value, such as specimens collected by Charles Darwin. The museum is particularly famous for its exhibition of dinosaur skeletons and ornate architecture—sometimes dubbed a cathedral of nature—both exemplified by the large Diplodocus cast that dominated the vaulted central hall before it was replaced in 2017 with the skeleton of a blue whale hanging from the ceiling.

|

| the Natural History Museum in London on postmark of UK 1985 |

The new museum was built, because the collection of the British Museum, established in 1753, which includes not only natural history objects, grew too much and the building filled up to the point where new specimens had to be turned away. Many new objects came from all over the world, but particularly from territories forming the British Empire and countries with strong trade with Britain such as China and USA. In the middle of the 1800s, after extensive debates, the decision was made to remove all the natural history collection to a separate museum. The Superintendent of the British Museum, Richard Owen, believed the world's powerful nation should have the wold's biggest and best natural history museum. Owen, who had connections with the Royal Family, convinced the government to construct a new building for the Museum.

In 1862 the government purchased land to build new museum in South Kensington. Due to the various political and technical issues, the construction of the new museum was started in 1873, based on the plans proposed by Richard Owen. The "cathedral to nature" was built by young, and at that time unknown, architect Alfred Waterhouse, who brought to life Owen's dream of a cathedral to nature. Waterhouse created wonderful depictions of plants and animals to decorate the building both inside and out. The decorations were carefully checked by Owen, and reflected his plan to divide the Museum display rigorously between past and present, with living creature to the west, fossils, rocks and minerals to the east.

Easter Monday, 18th April 1881, was the opening day of the British Museum (Natural History). Moving the natural history collection from the old building took more than a year. The last part of the zoological collection arrived in Late 1882. A new building, called the Darwin Center, was added to the Museum in 2002.

Since the openings and till today the museum is free of charge.

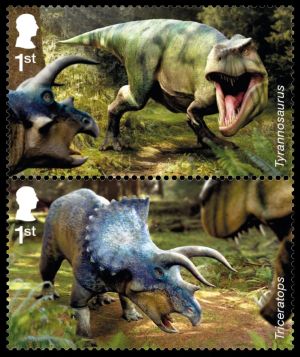

The first pair of "the Age of the Dinosaurs" stamps shows Tyrannosaurus facing off against a Triceratops, both lived during the Late Cretaceous between 68 and 66 million years ago in North America. A partial Triceratops fossil collected in 1997 has a horn that was bitten off, with bite marks that match Tyrannosaurus.

|

| Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops on the Age of the Dinosaurs stamps of Great Britain 2024 MiNr.: 5383-5384, Scott: |

From nose to tail, Tyrannosaurus reached up to 13 metres. Its skull alone could be 1.5 metres long. But despite this dinosaur's large body size, it had particularly tiny arms. Tyrannosaurus is the best-known dinosaur for the public. The skeletons or casts of this dinosaur can be seen in many museums in the world, including the Natural History Museum in London.

Tyrannosaurus was the largest dinosaur in the family Tyrannosauridae. Following close behind in size are other tyrannosaurs such as Tarbosaurus, Albertosaurus and Yutyrannus.

Some Tyrannosaurus fossils show bite marks from other tyrannosaurs, so it is clear that they fought each other, whether over food or mates. We know that close relatives of Tyrannosaurus sometimes lived together because there are fossils of groups who were buried together, but we don't know for sure if they hunted alone, or in packs like lions and wolves do today. So far, no groups of Tyrannosaurus skeletons have been found.

The collection of Natural History Museum in London includes the first known specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex, which was discovered in Wyoming, USA, the lower jaw of which is on display in the Dinosaur Gallery with a full-sized animatronic model of a Tyrannosaurus rex.

Triceratops was one of the biggest horned dinosaurs. It lived around 68 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous, alongside the likes of Tyrannosaurus. Triceratops weighed about 5 tonnes and measured up to 9m in length – its head alone was about as long as a person. It had a curved, bony frill jutting out over its neck and a hard beak at the end of its nose. The word Triceratops means "three-horned face" – a reference to its impressive horns, which may have been used in defence against large meat eaters.

The first Triceratops bones were found in Colorado, USA in 1887, and at first the pair of brown horns attached to a piece of skull were mistakenly thought to belong to a large and unusual bison.

The collection of Natural History Museum in London includes large skull of a Triceratops and a cast of a skeleton. The skull was collected by professional fossil collector Charles H Sternberg in 1909 at the Hell Creek Formation in Wyoming, USA.

The skeleton's cast a papier-mache model created by Frederic Lucas in 1900 for the Smithsonian display at the Pan-American Exhibition in Buffalo, New York. Lucas, probably, used illustration of a Triceratops skeleton from O.C. Marsh’s publication as the reference. Later, the Natural History Museum in London purchased the cast.

The second pair of "the Age of the Dinosaurs" stamps shows Stegosaurus and Diplodocus - another pair of North American dinosaurs from the Jurassic Period. Stegosaurus is one of the most recognisable dinosaurs, although we know relatively little about it as remains are rare. Diplodocus reached up to 27 metres in length and was one first sauropods discovered.

|

| Stegosaurus and Diplodocus on the Age of the Dinosaurs stamps of Great Britain 2024 MiNr.: 5387-5388, Scott: |

Fossils of the genus have been found in the western United States and in Portugal.

Various ideas have been proposed for the function of the plates. Perhaps they were used to defend against attack by predators, or acted as giant radiators, as the plates contained many blood vessels, to help Stegosaurus lose and gain heat - or maybe they were simply used for display.

Stegosaurus was slow moving plant-eater (herbivore) dinosaur, who had two pairs of pointed bony spikes were present on the end of the tail. These are presumed to have served as defensive weapons, as protection against predators, such as Allosaurus (Tyrannosaurus didn't evolved at the time Stegosaurus lived).

The forelimbs of Stegosaurus were much shorter than the hind limbs, which gave the back a characteristically arched appearance. The feet were short and broad. Stegosaurus's length estimated between 6 and 9 meters and the weight over 4.5 tons.

The long and narrow skull was small in proportion to the body. The skull's low position suggests that Stegosaurus may have been a browser of low-growing vegetation. Stegosaurian teeth were small, triangular, and flat; wear facets show that they did grind their food.

Despite the animal's overall size, the braincase of Stegosaurus was small, the smallest proportionally of all dinosaur endocasts then known. The brain of the 5 tonnes dinosaur was about 80g only. According to recent research, Stegosaurus didn't live in herds, but was probably solitary or lived in small groups.

|

| Stegosaurus on stamp of USA 1989, with omitted black color/text (MiNr.: 2053, Scott: 2424). |

Although Stegosaurus has been known for more than 130 years, not much is known about its biology, as fossils of Stegosaurus are rare. Only a few more or less complete skeletons of these dinosaurs have been discovered to date (2024).

The collection of the Natural History Museum in London includes the most intact Stegosaurus stenops skeleton, only a few bones are missing (left forelimb, the base of its tail, and a few other small bones). Despite its status as one of the most iconic and easily recognizable dinosaurs, well-preserved remains of Stegosaurus are surprisingly rare. It appears to have been so well preserved because it was buried rapidly in a pond or body of standing water immediately after death.

The unprecedented specimen, unearthed in Wyoming, USA in 2003.

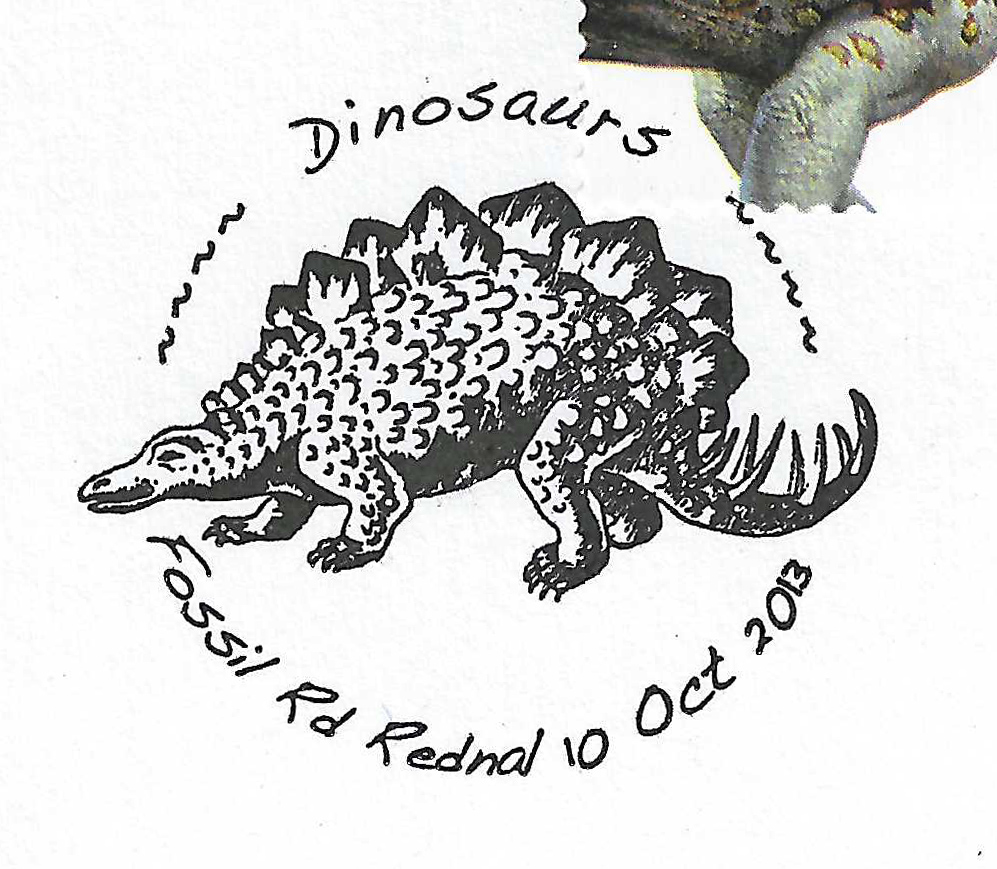

|

| Stegosaurus on postmark of UK 2013 |

The specimen was discovered in 2003 by Bob Simon who, late one evening during a severe windstorm, was moving a bulldozer and accidentally grazed the side of a hill. The next morning, Mr. Simon noted bones at the site where the bulldozer had accidentally removed some weathered material, and started to excavate what he later recognized as the base of a tail. Poor weather prevented more extensive exploration of the discovery that year and the remainder of the specimen was excavated in 2004 by Mr Simon, his staff, and Kirby Siber and colleagues from the Sauriermuseum, Aathal, Switzerland, where the specimen was later prepared.

It took 18 months to dig the fossil out of the ground. The fossils were purchased by the Natural History Museum in London and arrived at the Museum in late 2013. It took many months for the Museum's staff to assemble more than 300 bones. On 4th December 2014, the skeleton was added to the public gallery in the Earth hall of the Museum.The skeleton, is probably belongs to a young dinosaur, as it is just over 5.5 metres long, whereas other Stegosaurus specimens reach up to 9 metres in length.

Even though the sex of the dinosaur is unknown it received the nickname "Sophie", after daughter of Jeremy Herrmann who was the most notable donor in the purchase campaign of the Museum.

Diplodocus was one of the longest dinosaurs ever to have existed, Diplodocus was a long-necked prehistoric creature belonging to a group of dinosaurs called sauropods. It lived 150 million years ago at the end of the Jurassic Period. Reaching up to 27m in length, Diplodocus was a giant, weighing around 20 tonnes – as much as three male African elephants.

|

| Diplodocus chevrons. Image credit Wikipedia |

Diplodocus had a long neck that it would have used to reach high and low vegetation, and to drink water. There has been some debate over how such a long neck would have been held. Scientists now think that ligaments running from the hip to the back of the neck would have allowed Diplodocus to hold its neck in a horizontal position without using muscles.

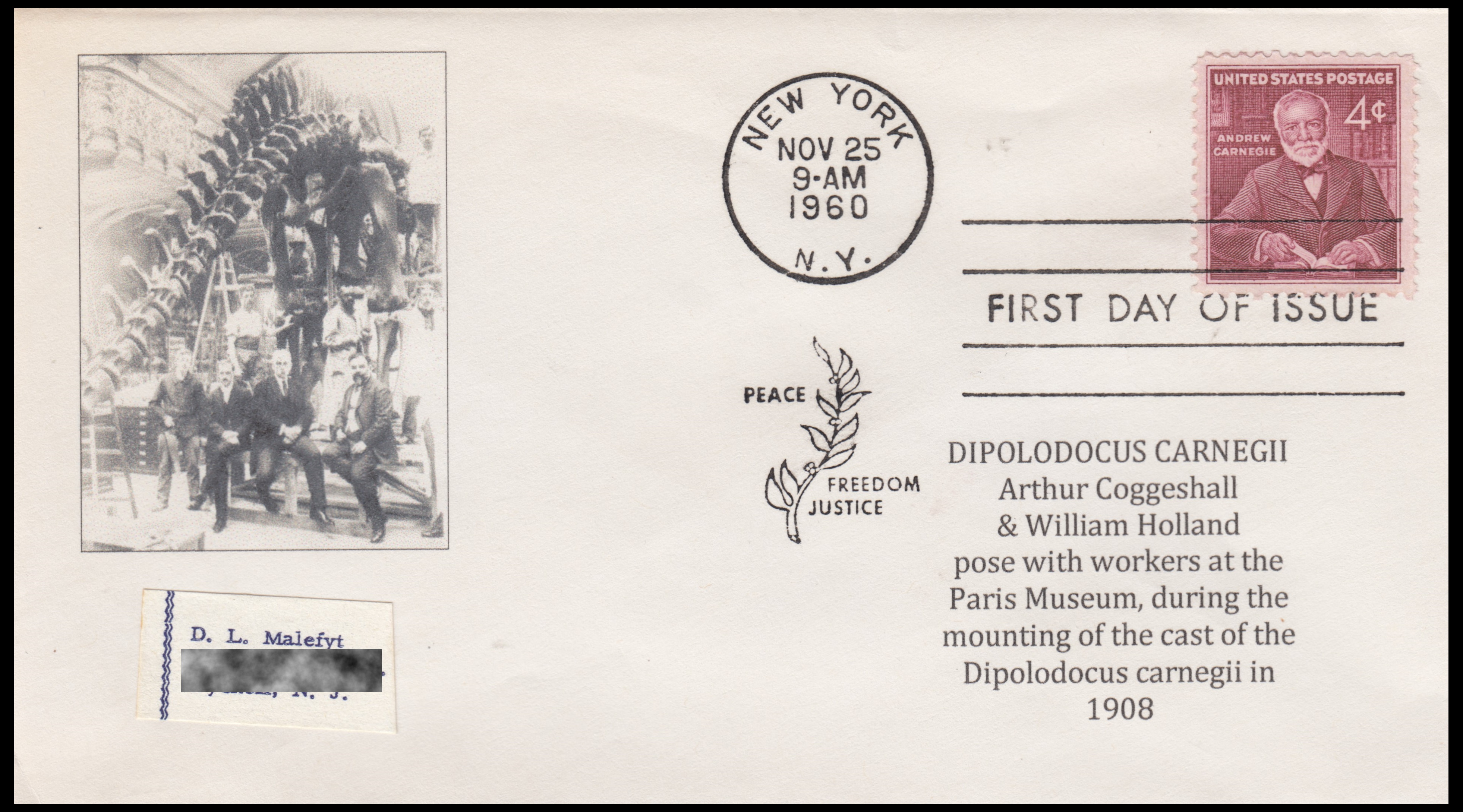

Collection of the Natural History Museum in London includes a cast of the famous Diplodocus - the "Dippy", who served as an awe-inspiring welcoming sight for visitors to the Museum from 1979 to 2017.

In 1905 a cast of a Diplodocus carnegii (named after Andrew Carnegie, who founded the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 1896) skeleton was donated to the Museum by the wealthy businessman Andrew Carnegie, based on the original specimen in the Carnegie Museum in the USA.

|

| Diplodocus carnegii on cachet of FDC with stamp of Andrew Carnegie, USA 1960 (MiNr.: 801, Scott: 1171). |

The first fossils of Diplodocus were discovered in 1877 in Colorado, USA

and was first described as a new type of dinosaur in 1878 by Professor Othniel

C Marsh at Yale University.

The most notable Diplodocus find came in 1899, when crew members

from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History were collecting fossils in the

Morrison Formation of Sheep Creek, Wyoming, with funding from Scottish-American

steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie, they discovered a massive and well preserved

skeleton of Diplodocus.

A series of casts of the specimen were made and donated by Andrew Carnegie to

different countries in Europe, including Berlin

and London and Latin America, including Mexico.

The goal of Carnegie in sending these casts overseas was apparently to bring

international unity and mutual interest around the discovery of the dinosaur.

Diplodocus, Dippy, on display in Hintze Hall of the Natural History Museum in London. Image credit: NHM UK

In January 2017, Dippy left the Museum to prepare for a natural history adventure across the UK. Today the Hall is occupied by skeleton of blue whale, with nickname "Hope", a 25-metre blue whale skeleton, suspended in the air.

After returning in 2022, the famous cast is now on display at the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum in Coventry, on long-term loan from the Museum.

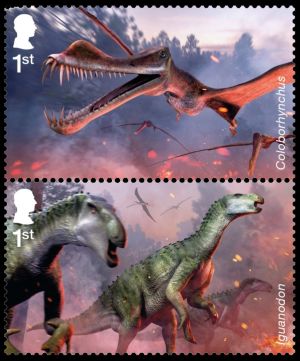

The third pair of "the Age of the Dinosaurs" stamps shows the pterosaur Coloborhynchus soaring through the sky over a herd of Iguanodons who lived during the Early Cretaceous between 125 and 110 million years ago in what is now England.

|

| Coloborhynchus and Iguanodon on the Age of the Dinosaurs stamps of Great Britain 2024 MiNr.: 5385-5386, Scott: |

Coloborhynchus was a type of pterosaur, a group of extinct flying reptiles that lived alongside the dinosaurs during the Mesozoic Era. Pterosaurs were the first vertebrates to achieve flight over 220 million years ago and included the largest flying creatures of all time. Coloborhynchus is known from the Lower Cretaceous of England, and it was once thought to be the largest known toothed pterosaur. The type specimen of Coloborhynchus is known only from a partial upper jaw (the jaw is in the collection of the Natural History Museum in London).

Comparing Coloborhynchus to other ornithocheirids suggests that its skull was about 30-35 cm long, and it had a wingspan of about 1.5 meters.

In 1874 Sir Richard Owen gave the name Coloborhynchus clavirostrus to a small fragment of an ornithocheirid pterosaur rostrum found in rocks of the Lower Cretaceous Hastings Beds of southern England. The genus name translates to “truncated snout,” referring to the flattened front edge of the specimen.

In Coloborhynchus, the two front teeth pointed forward and were higher on the jaw than the other teeth, while the next three pairs of teeth pointed to the sides. The final two (preserved) pairs of teeth pointed downward. Finally, a unique oval depression was located below the first pair of teeth.

The collection of the Natural History Museum in London still includes the fragment of the rostrum.

Iguanodon was a large ornithopod that lived during the Early Cretaceous between 125 and 110 million years ago, which are closely related to the hadrosaurs, or duck-billed dinosaurs.

Iguanodon was one of the first three dinosaurs to be named.

|

| Iguanodon on one of the "Dinosaurs" stamps of UK 2013, MiNr.: 3528, Scott: 3230. |

|

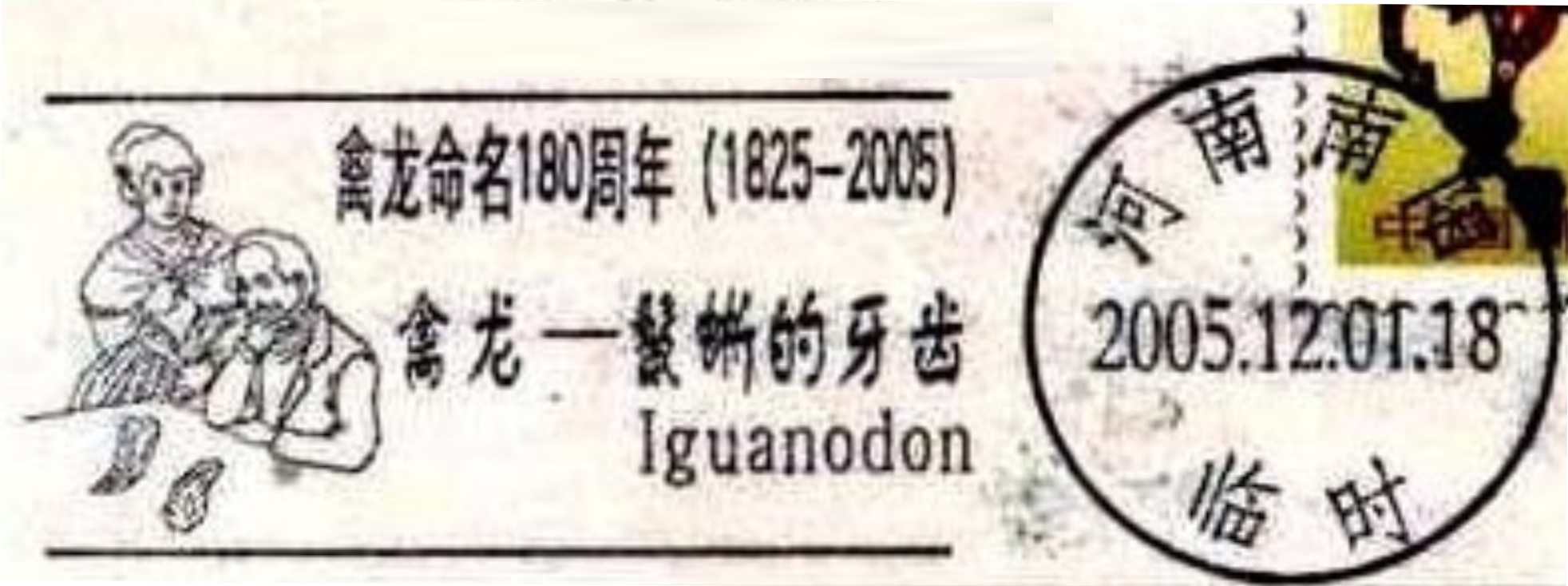

| Gideon and Mary Ann Mantell studying Iguanodon teeth on postmark of China 2005 |

|

| Gideon Mantell on meter-franking of South Korea 1995 |

|

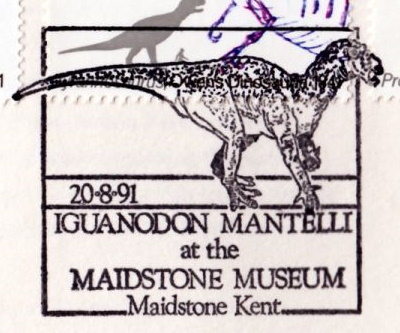

| Iguanodon mantelli at the Maidstone Museum, Maidstone, Kent on commemorative postmark of UK 1991 |

The teeth were ridged and formed sloping surfaces whose grinding action could pulverize its diet of low-growing ferns and horsetails that grew near streams and rivers. Most bones of the skull and jaws were not tightly fused but instead had movable joints that allowed flexibility when chewing tough plant material.

The fossil remains of many individuals have been found, some in groups, which suggests that iguanodontids travelled in herds. Fossilized tracks of iguanodontids are also relatively common and are widespread in Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous deposits.

The first fossil of this dinosaur was discovered in 1822 by Mary Ann Mantell (1795-1869). Mary Ann was a wife Dr. Gideon Algernon Mantell (1790-1852), who was an English surgeon, geologist and amateur palaeontologist.

Most accounts hold that Mary was accompanying her husband on a trip to visit a patient in Sussex, England, when she noticed something glinting by the side of the road. When Mary went to investigate, she discovered a collection of fairly large tooth embedded in the rocks.

The tooth is housed New Zealand's National Museum (Te Papa) today. After Gideon Mantell's death in 1852, the tooth was brought to New Zealand by his son Walter, who inherited his father's belongings in the 1850s, including the Iguanodon tooth. Walter Mantell built a career in the early colonial days of New Zealand (1840s to 1880s). A keen natural scientist, Walter helped establish the display of natural history objects - with the tooth in pride of place - when the Colonial Museum opened in 1865. This small and rather unprepossessing object is one of Te Papa's most valuable treasures, as it is one of the first fossils ever to be recognised as dinosaur and its discovery marked the beginning of dinosaur studies.

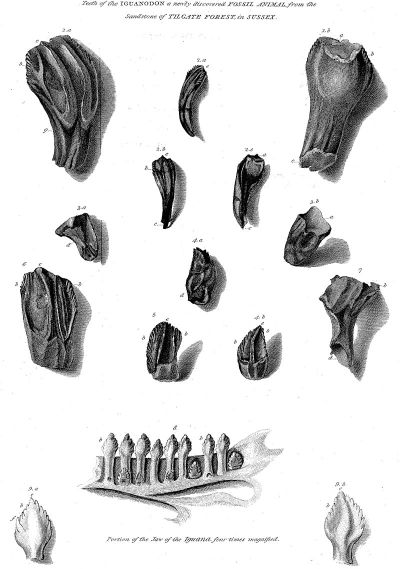

In May 1822 Dr. Gideon Mantell first presented the teeth to the Royal Society of London but the members, dismissed them as fish teeth or the incisors of a rhinoceros from a Tertiary stratum (an obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago). Even Georges Cuvier, who is sometimes referred to as the father of palaeontology, on his first examination of the tooth in 1822, didn't recognized it as a reptile tooth. He dismissed is as the teeth of a rhinoceros.Until that time, no evidence of giant prehistoric reptilian herbivores had been discovered. Remains of the large carnivore Megalosaurus had been in the collections of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History since the late 1600s, but they were only described by William Buckland in 1824 - two years after the discovery of these Iguanodon teeth.

In 1824, Mantell again sent some teeth to Cuvier, who answered that he had determined that they were reptilian and quite possibly belonged to a giant herbivore.

In a new edition that year of his "Recherches sur les Ossemens Fossiles" Cuvier admitted his earlier mistake, leading to an immediate acceptance of Mantell, and his new saurian, in scientific circles.

At that time Mantel had at least six Iguanodon teeth. At least two of them are in the collection of Natural History Museum (NHMUK) in London today. They were part of Mantell's private collection of fossils that was not catalogued until it was sold to the NHMUK and Mantell never explicitly published how much material of any species he owned.

|

|

| The Iguanodon tooth from the collection of New Zealand's National Museum (Te Papa). Image credit: Te Papa Museum. | The Iguanodon tooth from the collection of Natural History Museum (NHMUK) in London. Image credit: NHMUK in London. |

|

| This plate shows the Iguanodon teeth from Mantell’s 1825 paper. |

|

| Maidstone coat of arm with Iguanodon |

The fossilised teeth resembled those of the iguana, only many times larger. Iguanas are relatively large lizards, but scaled up the prehistoric owner of the fossilised teeth could have been up to 18 metres or longer. According to recent research this dinosaur reached a length of about 10 metres.

Mantell formally published his findings on 10 February 1825, when he presented a paper on the remains to the Royal Society of London. In this paper he described several prehistoric teeth from the Wealden district of East Sussex and called the prehistoric animal - Iguanodon. The Iguanodon name means iguana tooth.

Iguanodon was the second type of dinosaur formally named based on fossil specimens, after Megalosaurus (described in 1824 by William Buckland).

For several years Dr. Mantell searched for more evidence of Iguanodon. Although finds were plentiful, they were usually isolated bones and teeth. In 1834, portion of the skeleton of an extraordinary animal was discovered in a limestone quarry near Maidstone in Kent, by workmen accidentally blew up a slab of rock.

It was acquired by Mantell and known as the Maidstone Slab, or as the Mantell-piece. It contain many bones embedded in the rock: rib fragments, vertebrae, limb bones, parts of the pelvis as well as, crucially, part of a tooth and a clear impression of another.

Still encased in rock, the Maidstone skeleton is currently displayed at the Natural History Museum in London, formally labelled NHMUK 3741.

Due to the dinosaur's association with Maidstone and because of its importance to paleontology, the 1946 Maidstone Borough Council applied to have the dinosaur added to the Coat of Arms, and the request was approved by the Garter Principal King of Arms. Maidstone, the largest town in Kent, England with population approximately 117,000 people, is the only town in the Great Britain with a dinosaur on its coat of arms.

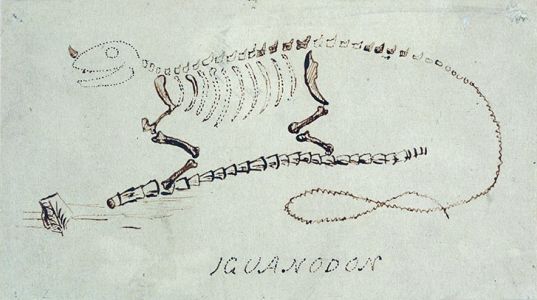

The Maidstone slab was utilized in the first skeletal reconstructions and artistic renderings of Iguanodon, but due to its incompleteness, Mantell made some mistakes, the most famous of which was the placement of what he thought was a horn on the nose.

|

|

| Gideon Mantell's Iguanodon restoration. Image credit: Wikipedia. | Statues in Crystal Palace Park based on the Maidstone specimen of "Iguanodon", designed by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, under supervision of Sir Richard Owen, after restoration in 2002. Image credit: Wikipedia. |

|

| Iguanodon thumb. Image credit: Wikipedia. |

|

| One of the Iguanodon skeletons on display a of the Royal Museum of Natural History in Brussels, on stamp of Belgium 1966, MiNr.: 1427, Scott: 664. |

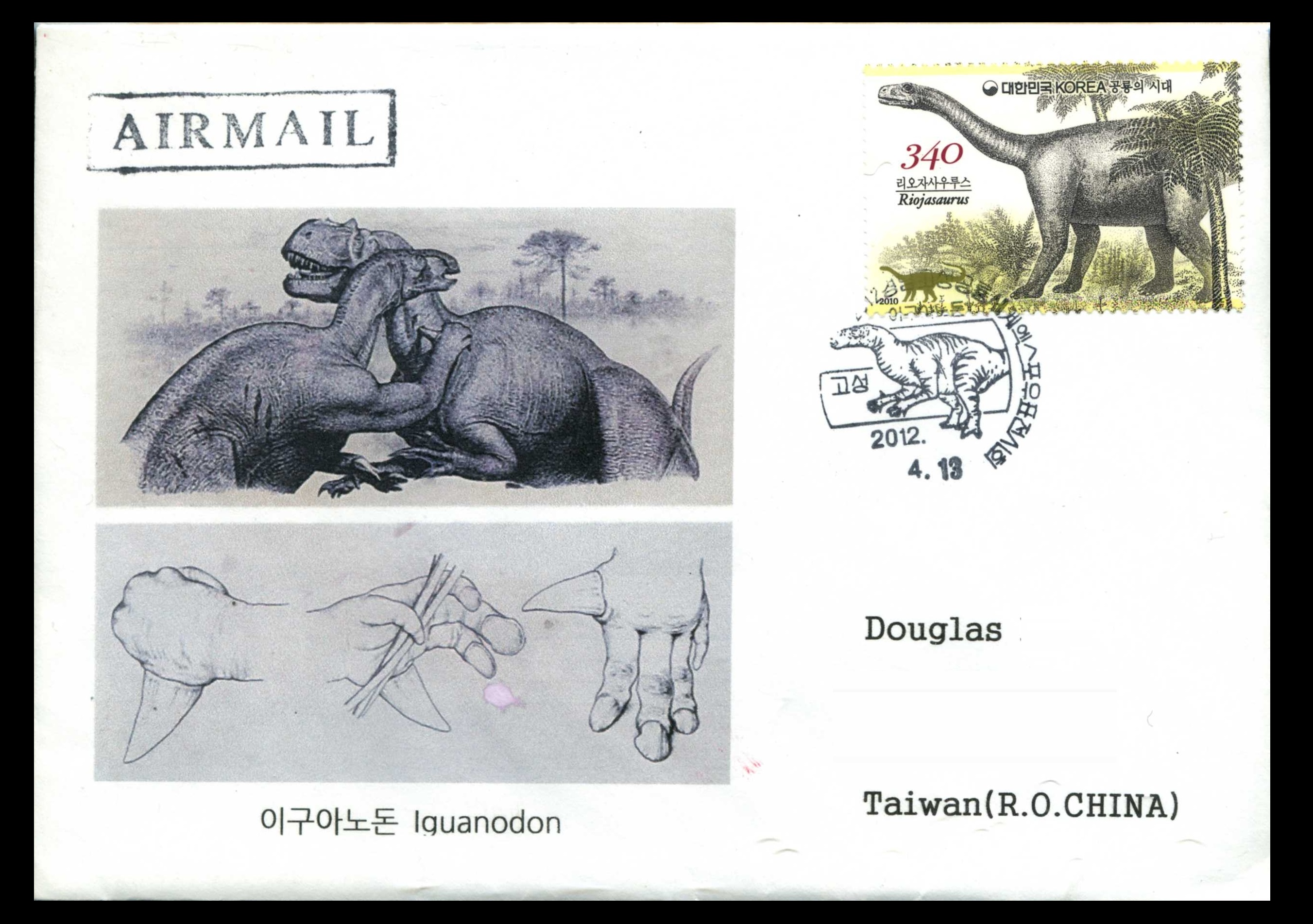

Iguanodon's hands were multifunctional. It had thumb spikes for food preparation or defence, three middle fingers fused into a 'hoof' for walking on and a fifth finger that was possibly used for grasping. Some scientists believe that the spiked thumbs were specialised tools, used for stripping foliage from branches or breaking into seeds.

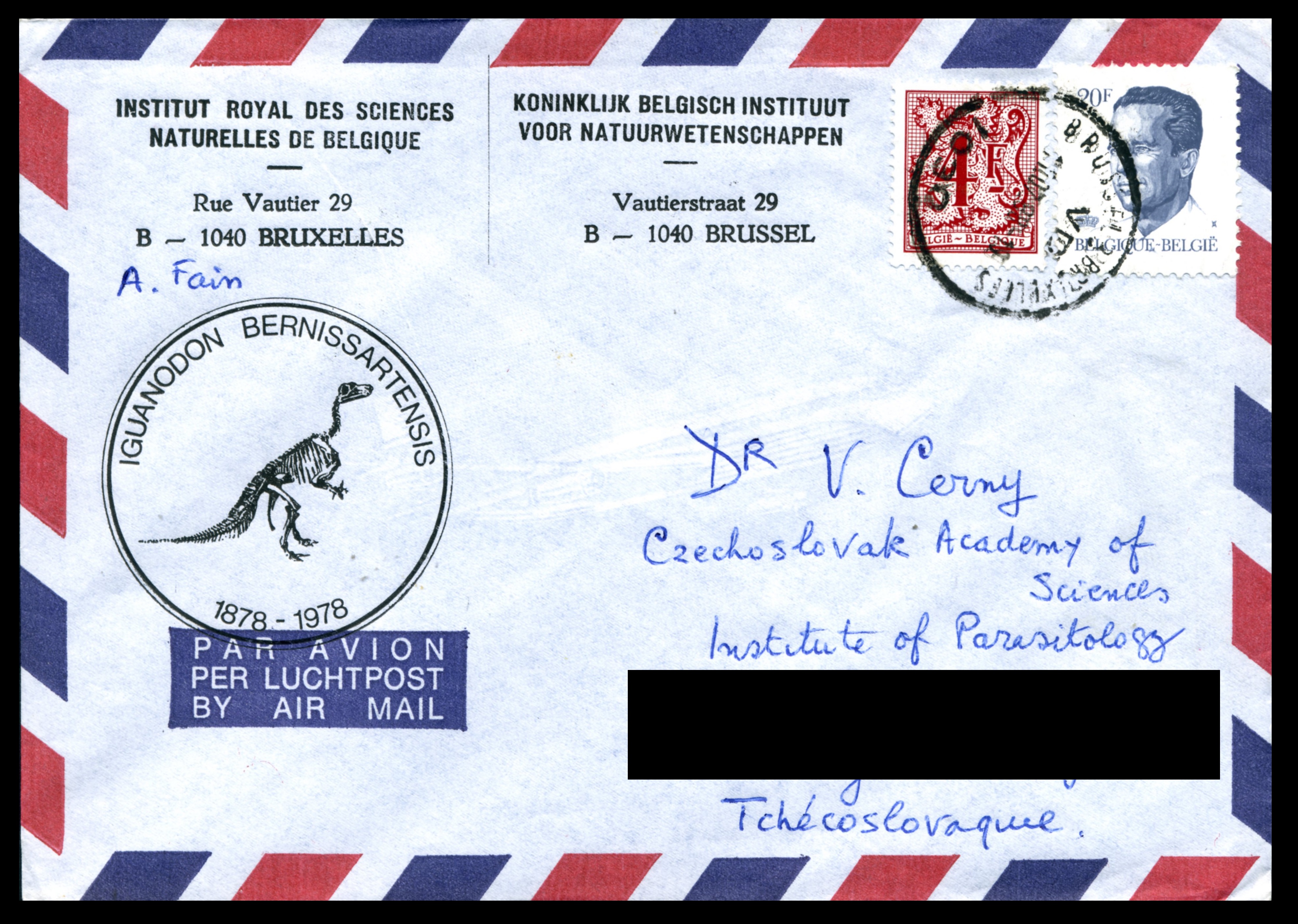

In 1878 over 30 relatively complete skeletons of Iguanodon were discovered by miners digging at 322 metres below the surface near the town of Bernissart, Belgium. This is the largest find of Iguanodon remains to date. Covered in plaster for protection and broken into 600 blocks, the fossils were transported to Brussels to be reassembled and fitted with iron frames. For the first time, scientists were able to see what a complete dinosaur might have looked like. The giant dinosaur puzzles were assembled based on knowledge of the time, by Belgian paleontologist Louis Dollo, that Iguanodon was bipedal, as it was believed the animal walk on two legs in a kangaroo-like posture.

More recent studies suggest that they were more likely to have walked on all four legs. The Belgian Iguanodon are now too fragile to be repositioned into life-like postures, however, so they remain a vestige of nineteenth-century thinking.

In 1883, the holotype specimen of Iguanodon bernissartensis became one of the first ever dinosaur skeletons mounted for display.

This specimen, along with several others, first opened for public viewing in an inner courtyard of the Palace of Charles of Lorraine in July 1883. In 1891 they were moved to the Royal Museum of Natural History, where they are still on display; nine are displayed as standing mounts, and nineteen more are still in the Museum's basement. The exhibit makes an impressive display in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, in Brussels. A replica of one of these is on display at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and at the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge, UK.

In 1825, when Mantell described the teeth, he neglected to add a specific name to form a proper binomial.

In 1829, Friedrich Holl added a specific name to the genus - Iguanodon anglicum, which was later emended to Iguanodon anglicus. In 1878 new, far more complete remains of Iguanodon were discovered in Belgium and studied by Louis Dollo.

|

| Iguanodon bernissartensis on the cachet of a cover of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. |

|

| Iguanodon on postmark and the cachet of the commemorative cover of South Korea 2012. The cachet shows an Iguanodon who uses its thumb for defence and forage purposes. |

Sir Richard Owen (1804-1892), who was one of the most famous comparative anatomists of his time, used Iguanodon (along with Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus) to coin the word 'dinosaur' in 1842 at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in London.

"Dinosauria" is rooted in Greek and frequently quoted as meaning 'terrible lizard'. But in coining the term in his report, Owen refers to dinosaurs instead as "fearfully great", acknowledging their large size - significantly surpassing that of any living reptile.

Although the fossil skeletons were far from complete, palaeontologists of the time attempted to work out the size of dinosaurs by scaling up living lizards. According to their estimates, some dinosaurs were 60 metres long.

Owen was skeptical of these massive sizes. Instead, he measured individual vertebrae and estimated their total number based on those of living crocodiles. This yielded more realistic lengths - around nine metres for Megalosaurus and Iguanodon.

In his proclamation of the new group Dinosauria, although referring to the animals as fossil lizards, Owen stated they were similar to pachydermal mammals (any of various nonruminant mammals such as an elephant, a rhinoceros, or a hippopotamus).

In 1849, a few years before his death in 1852, Mantell realised that iguanodonts were not heavy, pachyderm-like animals, as Owen was putting forward, but had slender forelimbs.

|

| Megalosaurus and Cryptoclidus on the Age of the Dinosaurs stamps of Great Britain 2024 MiNr.: 5389-5390, Scott: |

Megalosaurus was one of three species (along with Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus) that led paleontologist and anatomist Sir Richard Owen to coin the term "Dinosauria" back in 1841, when he realised that all three creatures shared common characteristics and were their own distinct group of reptiles. His paper sparked a fascination with dinosaurs that continues today.

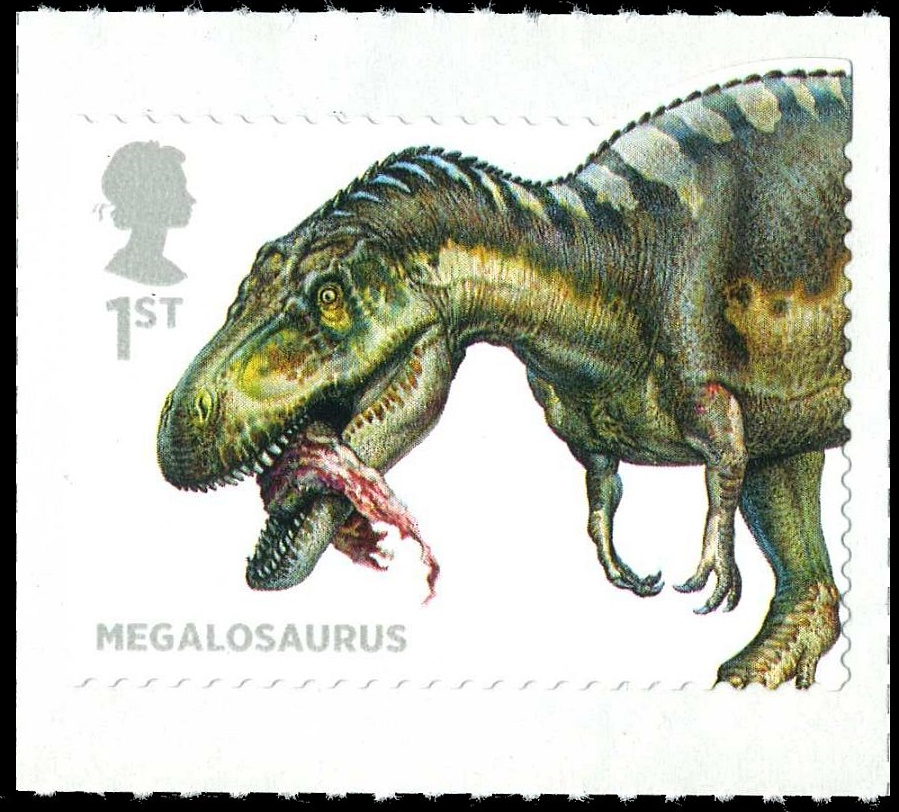

It was William Buckland, Professor of Geology at the University of Oxford and dean of Christ Church, who, in 1824, named the creature Megalosaurus. This was the first scientific description ever produced of what became known as a dinosaur.

In his description, Buckland didn't specify the species name. In 1827, Gideon Mantell included Megalosaurus in his geological survey of south-eastern England and assigned the species to Megalosaurus bucklandii.

Over 50 other species would eventually be classified under the genus; at first, this was because so few types of dinosaur had been identified, but the practice continued even into the 20th century after many other dinosaurs had been discovered. Today it is understood that none of these additional species was directly related to Megalosaurus bucklandii, which is the only true Megalosaurus species.

|

| Megalosaurus on one of the "Dinosaurs" stamps of UK 2013, MiNr.: 3534, Scott: 3236. |

|

| Megalosaurus on stamp of Romania 1994, MiNr.: 4975, Scott: 3901. |

|

| William Buckland and the Megalosaurus jaw on meter-franking of South Korea 2001 |

The most impressive of these fossils was a lower jaw fragment. The jaw was discovered about 12 meters underground in a Stonesfield Slate mine during the early 1790s. In 1805, a professor of anatomy brought Buckland a unique jawbone that he had bought in one of the many geological markets popular in England frequented by wealthy collectors.

As result of Industrial Revolution (from around 1760 to about 1820–1840), when people started to excavate fossils as result of deep digging for the roads and big building constructions. They reveal strata with increasingly longer timelines and a history.

But it wasn't until around 1818 that William Buckland, Gideon Mantell and several other naturalists began to study the remains in detail.

Buckland did not know to what animal the bones belonged but, in 1818, after the Napoleonic Wars, the French comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier visited Buckland in Oxford and realised that they were those of a giant lizard-like creature.

Buckland further studied the remains with his friend William Conybeare and referred to them as the "Huge Lizard".

William Daniel Conybeare FRS (1787 – 1857), dean of Llandaff,

was an English geologist, palaeontologist and clergyman.

He is probably best known for his ground-breaking work on fossils and excavation

in the 1820s, including important papers for the Geological Society of London

on ichthyosaur anatomy

and the first published scientific description of a plesiosaur.

In 1821 Conybeare together with Henry de la Beche (1796 - 1855)

named the first genus of Ichthyosaurus, based on

the name used by Charles Dietrich Eberhard Koenig, curator of the

Department of Natural History British Museum, in 1817

at "A Synopsis of the Contents of the British Museum".

In the following year Willian D. Conybeare and Henry de la Beche described

ichthyosaurs as reptiles,

based on the fossil found by Mary Anning

in 1821 and assigned ichthyosaurs to the Class Reptilia.

Buckland named the creature the bones belonged to Megalosaurus, or great lizard, in a scientific paper that he presented to London’s newly formed Geological Society on February 20, 1824. Buckland thought it was likely amphibious, living partially in land and water.

Almost all scientists at this time believed in the Divine creation of the Earth and its life and had difficulties finding an explanation for the extinction of the animal. It was a common belief at this time, that a God who created the world and all that was in it would not allow his creations to disappear from existence. All fossilized bones and tooth were assigned to either existing animals, crocodiles for example, animals dead in the biblical (Noah) flood or to remains of biblical titans.

|

|

Richard Owen's diagram of Megalosaurus, showing the fused sacral vertebrae.

This illustration was published in Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World in 1854. Image credit: NHM UK |

In the Garden of Eden, everything was peaceful and beautiful, and this carnivorous beast did not fit, it could not have been created by God. So, Buckland justified it by saying that it is a perfect killing machine, capable of causing death without pain, so God created it to eliminate suffering in an effective way.

With the help of other scientists including the famous French expert Georges Cuvier, Buckland came to think that the extinct animal might have been a huge lizard that walked on four legs, almost like an oversized iguana. Many years later the first fossils of bipedal dinosaurs were discovered, making it clear that Megalosaurus walked on two legs. A complete Megalosaurus skeleton has yet to be found. Buckland estimated the size of Megalosaurus of 20 metres long.

In 1842, Richard Owen gave a smaller estimate of 9 metres long. According to latest research, paleontologists think it was more likely to have been around 6 metres long, weighing about 700 kilograms.

Historically, artists have often portrayed Megalosaurus together with Iguanodon, as the two dinosaurs were among the earliest discovered. But they didn't live at the same time. Megalosaurus would have been extinct by the time Iguanodon appeared in the Early Cretaceous.

|

|

| The jaw used by William Buckland to describe Megalosaurus. Image credit: Wikipedia | 1854 reconstruction in Crystal Palace Park guided by Richard Owen presents Megalosaurus as a quadruped. Image credit: Wikipedia |

Due to the fragmentary nature of what paleontologists know to be Megalosaurus, paleontologists don’t know a lot about this dinosaur’s biology. What paleontologists know of the megalosaur family largely comes from more complete related taxa such as Afrovenator and Torvosaurus.

|

| Pangea, an ancient supercontinent, on stamp of San Marino 2008, MiNr,: 2337, Scott: 1749 . |

The dinosaur was bipedal, walking on stout hindlimbs, its horizontal torso balanced by a horizontal tail. Its forelimbs were short, though very robust. Megalosaurus had a rather large head, equipped with long curved teeth. It was generally a robust and heavily muscled animal. The jaws carried long serrated bladelike teeth, much like those of Allosaurus and other large theropods, to which it must have been closely related.

The collection of the Natural History Museum in London includes many disarticulated fossils of Megalosaurus. The jaw is in the collection of Oxford University Museum of Natural History however.

Cryptoclidus was a type of plesiosaur (not a dinosaur) – a group of extinct marine reptiles that existed from the Middle Triassic to the Late Cretaceous, known from fossils discovered in England, France, and Cuba.

|

| Cryptoclidus on stamp of Poland 1965 on one of the "Prehistoric Animals" stamps of Poland 1965, MiNr.: 1571, Scott: 1308. |

Plesiosaurs have been described as looking like a "snake threaded through a turtle".

Their limbs were large, well-developed paddles and it is thought

that they flapped these up and down in a similar way to a turtle.

Plesiosaurs would have been found across the world, including in what is now

Argentina,

USA,

Australia,

France,

Germany,

China and

Morocco.

Plesiosaurs were among the first fossil reptiles discovered.

The first two plesiosaur skeletons ever found in 1821 and 1823,

by Mary Anning at Jurassic marine strata at Lyme Regis

in England.

The first plesiosaurian genus, the eponymous Plesiosaurus, was named in 1821,

by William Conybeare and Henry Thomas De la Beche.

Cryptoclidus was a plesiosaur whose specimens include adult and juvenile skeletons, and remains which have been found in various degrees of preservation.

Cryptoclidus was a heavy-bodied, long-necked plesiosaur with a shortish tail and a broad, lightly built skull, with as many as 100 small sharp teeth that interlocked outside the jaws. This uncommon arrangement is believed to have functioned as a sort of trap for fishes and soft-bodied cephalopods.

The first fossil of Cryptoclidus was discovered as early as 1870s. The type species was initially described as Plesiosaurus eurymerus by Phillips in 1871.

|

| Cryptoclidus on stamp of Romania 1993, misnamed Plesiosaurus, MiNr.: 4912, Scott: 3846. |

|

| Young individual of Cryptoclidus in the Natural History Museum, London. Image credit: Plesiosauria.com |

In 1892, Harry Seeley first described Cryptoclidus ("hidden clavicle"), named for the small clavicle bones that rest in shallow depressions on the inner surface of the front limb girdle and are thus hidden from view. Seeley's actual specimen, found in the Oxford Clay of Bedford, England, has been lost.

Cryptoclidus was a medium-sized plesiosaur, with the largest individuals measuring up to 4 meters long and weighing about 737–756 kg.

The fragile build of the head and teeth preclude any grappling with prey, and suggest a diet of small, soft-bodied animals such as squid and shoaling fish.

Cryptoclidus may have used its long, intermeshing teeth to strain small prey from the water, or perhaps sift through sediment for buried animals. This genus had characteristic teeth with reduced ornamentation.

Their necks were not very flexible. Paleontologists have concluded that this long neck kept their bulky body away from its head so as to prevent their prey from being alerted.

Fossil studies indicate that Cryptoclidus had four broad limbs which were paddle shaped. These specialized legs helped them to "fly" through the water in the undulations which were caused by the waves. The flattened body shape provides additional dorsoventral stabilization during subaqueous flight locomotion as in marine turtles. There also have been other school of thoughts who have concluded that the Cryptoclidus swam like a porpoise. They probably had an upward movement with the two flippers and gliding backwards with the other two pairs.

Fossils of Cryptoclidus are relatively common, and provide a complete ontogenetic sequence from very young to old adult individuals. This makes Cryptoclidus one of the most studied and best understood of all plesiosaurs.

Full mounted skeletons of Cryptoclidus can be seen in several major museums including the Musee Palaeontologique, Paris; the Natural History Museum, London; the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow; and the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Products and associated philatelic items

| FDC of Royal Mail | Presentation Pack | |

|

|

|

| The same cover, but different postmarks: Ammonite of Lyme Regis and dinosaur footprints from London. | A fact-packed foldout souvenir containing stamps, images and insights into different prehistoric species. | |

| Stamp Sheets | Coin Covers | |

|

|

|

| These sheets were offered by Royal Mail as full (60 stamps) and half size (30 stamps). |

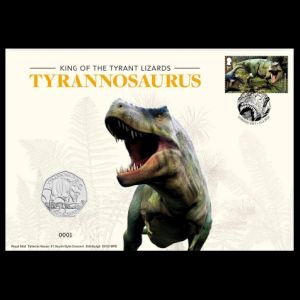

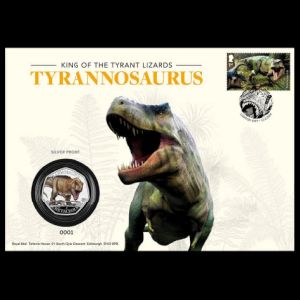

A limited-edition souvenir released in partnership with The Royal Mint and the Natural History Museum.

Includes the Tyrannosaurus stamp cancelled with a bespoke handstamp. The cover on the left - a limited-edition of 5,000 with 50p coin in immaculate Brilliant Uncirculated condition. the cover on the right - a limited-edition of 1,000 with 925 Ag silver 50p coin includes selective colourisation. The reverse side of the cover and the information card contain some details about Tyrannosaurus. |

|

| Postcards | ||

|

|

|

| The reverse side is here | ||

| First-Day-of-Issue Postmarks | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Customized FDC | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Regular letters sent on the day of the stamps issue, cancelled with commemorative postmarks. To protect these covers from any damage the Royal Mail sent them in plastic bags. The marks made by the mail sorting machine and by the postman were marked on the plastic bag, making it difficult to prove that these covers had gone through the mail. | |||

Some Books about Natural History Museum in London

|

|

|

|

|

"Richard Owen: Biology without Darwin" Amazon: USA, UK, DE. |

"Treasures of the Natural History Museum" Amazon: USA, UK, DE. |

"Natural History Museum: Souvenir Guide" Amazon: USA, UK, DE. |

"Nature's Cathedral: A guide to the Natural History Museum building" Amazon: USA, UK, DE. |

References:

|

|

|

"The Dinosaur Hunters: A True Story of Scientific Rivalry and the Discovery of the Prehistoric World",

Deborah Cadbury. Amazon: USA, UK, DE. |

- Technical details and short press releases:

- Artist: Joshua Dunlop

- Stamp Design: "The Chase" creative constructing: official website

-

Natural History Museum UK:

- official website

- "The Museum's dinosaurs"

- "Dinosaur collection" of NHM UK

- "Dinosaurs in England"

- Wikipedia

-

"Treasures of the Natural History Museum", published by Natural History Museum UK in 2009, ISBN 0565092359.

Amazon: USA, UK, DE. -

"Natural History Museum: Souvenir Guide", published by Natural History Museum UK in 2017, ISBN 0565094181

Amazon: USA, UK, DE. -

"Nature's Cathedral: A guide to the Natural History Museum building", published by Natural History Museum UK in 2021, ISBN 0565094831

Amazon: USA, UK, DE.

Prehistoric animals depicted on the stamps

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acknowledgements:

- Many thanks to Mr. Joshua Dunlop for a nice chaton Facebook and permission to use his images and sketches in this article.

- Many thanks to Dr. Peter Voice from Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Western Michigan University, for his help to find an information for this article, the draft page review and his very valuable comments.

| <prev | back to index | next> |