UK 2024

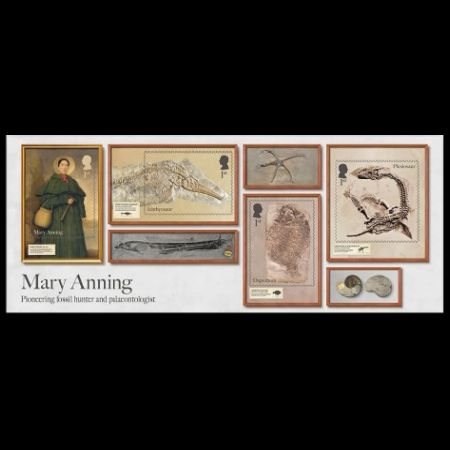

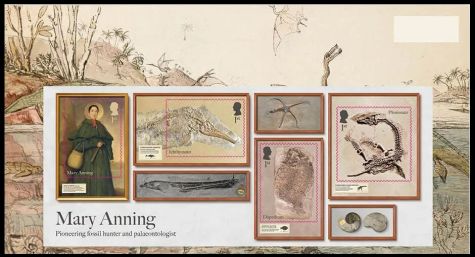

"Mary Anning pioneering fossil hunter and palaeontologist"

(part II of "The Age of the Dinosaurs" issue)

| <prev | back to index | next> |

| Issue Date | 12.03.2024 |

| ID |

Michel: Bl. 171 (5391-5394); Scott: Stanley Gibbons: Yvert: Category: pR |

| Design | The Chase creative consultants, UK |

| Stamps in set | 4 |

| Value |

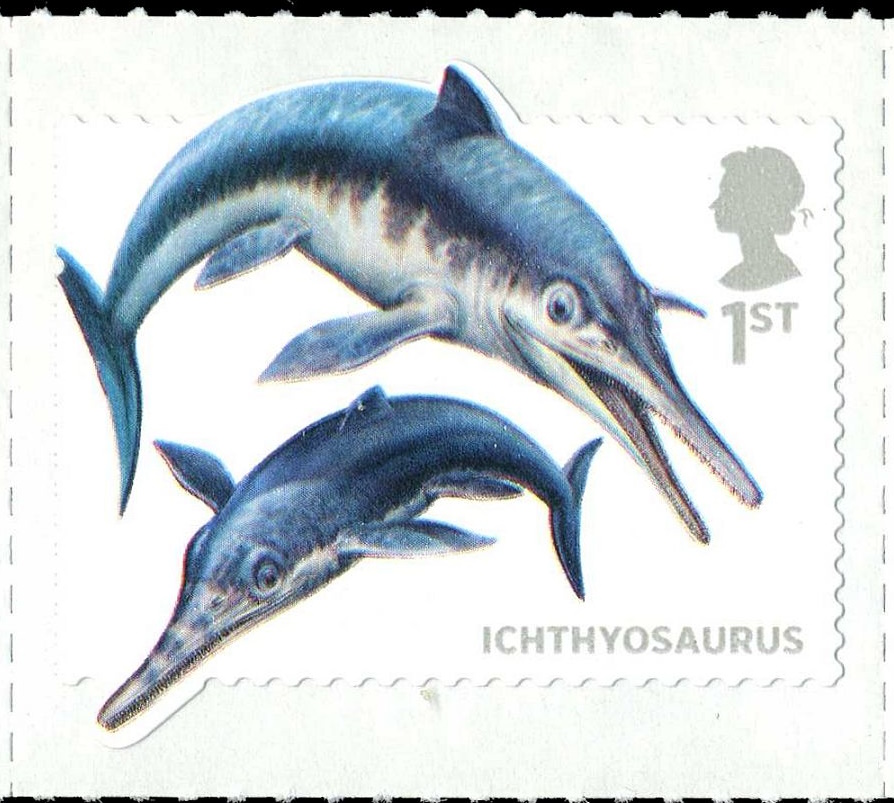

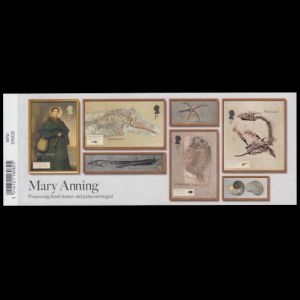

First Class - Mary Anning: portrait First Class - Ichthyosaur First Class - fish Dapedium First Class - Plesiosaur First Class rate was equivalent to GBP 1,25 Brittle stars, ammonite and a jaw of a pterosaur depicted on selvages of the Mini-Sheet. |

| Emission/Type | commemorative |

| Issue place | London, Lyme Regis |

| Size (width x height) |

Mini-Sheet: 180mm x 74mm stamps: Mary Anning and Dapedium - 27mm x 37mm Ichthyosaurus - 37mm x 27mm Plesiosaurus - 35mm x 35mm |

| Layout | Mini-Sheet of four self-adhesive stamps and three labels. |

| Products | FDC x2, PP x1, Uncut Mini-Sheets. |

| Paper | self-adhesive |

| Perforation | Plesiosaur 14.5 x 14.5, other stamps: 14.0 x 14.0 |

| Print Technique | Lithography |

| Printed by | Cartor Security Printers |

| Quantity | |

| Issuing Authority | Royal Mail |

On March 12th, 2024, the Royal Mail of the Great Britain issued the stamps set "The Age of the Dinosaurs".

The set includes

- four pairs with reconstructions of prehistoric animals, mostly dinosaurs

- the Mini-Sheet show Mary Anning and some of the most important fossil discovered by her.

This article is about the self-adhesive stamps of Mary Anning pioneering fossil hunter and palaeontologist, who has the 225th birth anniversary in 2024. The Mini-Sheet contains four self-adhesive stamps and three labels.

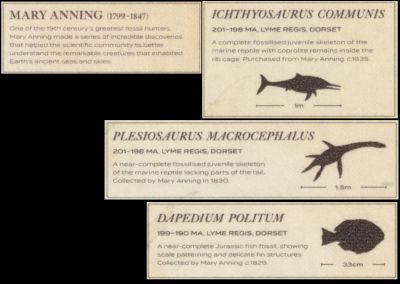

The portrait of Mary Anning and each of her discoveries are presented within picture frames in the Mini-Sheet with captions written in microtext which can be read under a magnifying glass, or on computer after scan it in very high resolution.

These stamps shows:

|

|

The labels show fossils of

|

The Mesozoic Era, or the "Age of the Dinosaurs" as it is commonly known, lasted from 252 to 66 million years ago and comprises, in order from oldest to youngest, the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. During most of this time, from the Late Triassic onwards, a group of reptiles known as dinosaurs dominated the land. Other non-dinosaur reptiles also thrived during this period, including marine reptiles, such as ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, as well as the flying pterosaurs.

The "Age of Reptiles", the term introduced by Gideon Mantel at the end of 1820s, would be more precise to define the Mesozoic Era.

Fossilised remains help paleontologists to unearth the secrets of these incredible creatures, and one of the greatest fossil hunters of the 19th century was Mary Anning.

The photo of portrait of Mary Anning, fossils of Ichthyosaur, Plesiosaur, brittle stars and pterosaur's jaw, were provided by the Trustees of the Natural History Museum of London. The photo of prehistoric fish Dapedium was provied by Oxford University Museum of Natural History and the photo of Ammonite was provided by Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society and South West Heritage Trust.

Anning's discoveries of ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs and pterosaurs on the Dorset coast, near her home in Lyme Regis, paved the way for modern paleontology and contributed to the understanding of prehistoric life on Earth.

In 2001, the Stundland Bay in Dorset was designated as the Jurassic Coast

World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

"The cliff exposures along the Dorset and East Devon coast provide an almost

continuous sequence of rock formations spanning the Mesozoic Era, or some 185

million years of the earth's history.

The area's important fossil sites and classic coastal geomorphologic features have

contributed to the study of earth sciences for over 300 years."

Mary Anning was also famous and honored by her contemporaries.

Despite her lack of formal scientific training, her discoveries, local area knowledge, and skill at classifying fossils in the field earned her a reputation among paleontology’s male and largely upper-class ranks. Her excavations aided the careers of many British and oversea scientists by providing them with specimens to study and framed a significant part of Earth’s geologic history.

|

| The label attached to a one of the brittle stars, in NHM UK, formerly the British Museum, mention Mary Anning as saler of the fossil. Image credit: Data Portal of NHM UK. |

|

|

The bronze statue of Mary Anning, at Long Entry, Lyme Regis, Dorset. Image credit: artuk.org (the website contain many photos of the statue from different angles and zooms, allows to get very detailed impression) |

|

| One of the £50 banknote proposial with the portrait of Mary Anning, but at the end Alan Turing, who is best known for his outstanding code-breaking which was vital to the Allied victory in WWII, was selected. |

She corresponded with many famous naturalists of her time in England and abroad, such as:

William Buckland, who described the first dinosaur - Megalosaurus,

Gideon Mantell, who described Iguanodon - the second described dinosaur,

Sir Richard Owen, who coined the word Dinosaur and who initiated the construction of Natural History Museum in London,

Georges Cuvier, who sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology",

Adam Sedgwick, who taught geology at the University of Cambridge and who numbered Charles Darwin among his students and many others. She even took Richard Owen on a guided fossil hunting tour of the Blue Lias, and in 1844, the King of Saxony visited her shop.

However, she was not directly credited with her finds in publications of many prominent scientists who described the fossils purchased from her in prestigious journals without even a mention of her name.

Male scientists - who frequently bought the fossils Mary would uncover, clean, prepare and identify - often did not credit her discoveries in their scientific papers on the finds, even when writing about her groundbreaking ichthyosaur find.

In the book "The Fossil Remains of Animal Kingdom", published in 1830 in London, as a supplementary volume to "The Animal Kingdom arranged in conformity with its organization by the Baron Cuvier" translated and written by Edward Griffith, its author, Edward Pidgeon wrote:

...

This very perfect and highly interesting specimen of the

remains of an ichthyosaurus was discovered in February,

1829, by Miss Anning; nor can we suffer the present opportunity to pass

by without bearing testimony to the arduous and zealous exertions of

this female fossilist in her laborious and sometimes dangerous pursuit.

It is to her almost exclusively that our scientific countrymen, whose names

have been already mentioned, owe the materials on which their labours and

their fame are grounded, nor, we are persuaded, will they be

unwilling to admit that they are indebted for some portion of

their merited reputation to the labours of Mary Anning.

The first time her name was formally recorded as a collector of a specimen acquired by a museum was in October 1840, when the British Museum purchased three fossil of brittle stars from her as was recorded in the museum's catalogue:

"Species of Ophiura erengtoni, Lower Jurassic, Blue Lias, Lyme Regis, Dorser, purchased: Miss M. Anning, 1840" (see on the right).

Some science historian note that fossils recovered by Anning may have also contributed, in part, to the theory of evolution put forth by English naturalist Charles Darwin. Her name was known to Darwin, who probably never meet her, but who was presented at the Annual General Meeting of the Geological Society, on 18th February 1848, as the Society's former Secretary.

At this meeting Henry De la Beche, the president of the Society, eulogized her in his annual address.

I cannot close this notice of our losses by death without adverting to

that of one, who though not placed among even the easier classes of society,

but who had to earn her daily bread by her labour, yet contributed by her

talents and untiring researches in no small degree to our knowledge of

the great Enalio-saurians

[an order of fossil marine reptiles, found in the liassic, triassic, and

cretaceous epochs], and other forms of organic life entombed in the

vicinity of Lyme Regis.

Mary ANNING was the daughter of Richard Aunig, a cabinet-maker of

that town, and was born in May, 1799.

While yet a child in arms (19th August, 1800), she narrowly escaped death,

when with her nurse taking shelter beneath a tree durimg a thunderstorm,

which had scattered a crowd collected in a field to witness some feats of

horsemanship to be performed by a party travellmg through the country.

Two women, with the nurse, were killed by the lightning, which struck

the tree beneath which they considered themselves safe; but the

child, Mary Anning, was by careful treatment revived, and found not

to have sustained bodily injury.

From her father, who appears to have been the first to collect and sell

fossils in that neighbourhood, she learnt to search for and obtain them.

Her future life was dedicated to this pursuit, by which she gained her livelihood;

and there are those among us in this room who know well how to appreciate

the skill she employed, (from her knowledge of the various

works as they appeared on the subject,) in developing the remains of

the many fine skeletons of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri, which without her care

would never have been presented to comparative anatomists in the uninjured form

so desirable for their examination.

The talents and good conduct of Mary Anning made her many friends ;

she received a small sum of money for her services, at the intercession

of a member of this Society with Lord Melbourne, when that nobleman was premier.

This, with some additional aid, was expended upon an annuity, and with it,

the kind assistance of friends at Lyme Regis, and some little aid derived from

the sale of fossils, when her health permitted her to obtain them, she bore

with fortitude the progress of a cancer on her breast, until she finally sunk

beneath its ravages on the 9th of March, 1847.

Mary Anning became her formal recognition at the end of her life and much more recently. In July 1846 (less than a year before her death), Mary Anning was elected as first honorary member of newly-established Dorset Country Museum.

In 2002, the Palaeontological Association of Great Britain established a new prize - the Mary Anning Award. The Award is given to outstanding contributions to paleontology made by amateurs.

In 2010, the Royal Society included Mary Anning among the 10 British women who have most influenced the history of science, and in 2018, portrait of Mary Anning was nominated to appear on a new 50 GBP banknote of Bank of England.

On 21st May 2019, at the 220th birthday of Mary Anning, 11 years old girl from Dorset, Evie Swire - a keen fossil hunter also from Lyme Regis, initiated crowdfunding campaign called "Mary Anning Rocks". The goal of the campaign was to collect the money to create and install a statue at Lyme Regis.

On 21 May 2022, Mary Anning’s 223rd birthday, four years after the campaign began, the bronze statue of Mary Anning, designed by the artist Denise Dutton, was unveiled on the seafront of Lyme Regis, the town in which she was born and lived.

The statue depicts Mary and her dog Tray, striding towards the beach, an ammonite in one hand and rock hammer in the other, with a basket on her arm. It is sited at Church Cliff beach, near to where Mary lived (see the photo of the statue above).

Prof. Richard Herrington, Head of Earth Sciences department at the Natural History Museum in London, says:

Mary Anning has left an impressive legacy in the study of palaeontology. Here at the Museum, we look after many of her most spectacular finds, including famous pterosaur, ichthyosaur and plesiosaur specimens. They are still studied by palaeontologists from all over the world, and her life continues to be an inspiration to young scientists even today.

Despite her discoveries being some of the most significant geological finds of all time, for a long period she was overlooked by the history books.

"I believe a permanent statue of her on the Jurassic coast would be a fitting tribute to a woman who changed the face of geology.

Who was the Mary Anning ?

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was one of two surviving children born to cabinetmaker and amateur fossil collector Richard Anning (1766 - 1810) and his wife, Mary Moore (1764 - 1842). She grew up in poverty and seldom escaped it during her short adult life, dying of breast cancer in 1847.

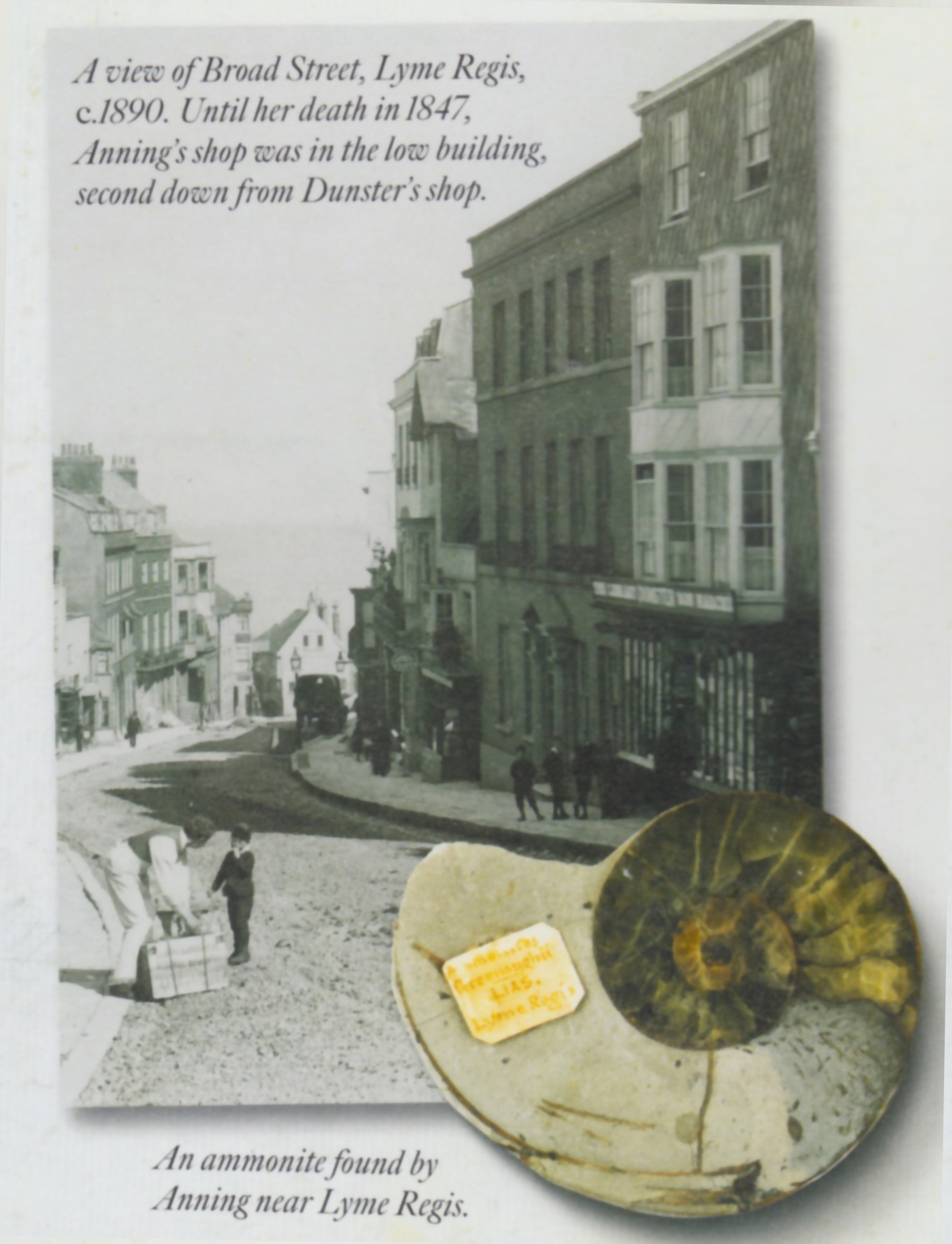

|

| The view on the street were Mary Anning was living. Image credit: presentation pack of the Royal Mail. |

|

Many fossls of marine prehistoric animals, includes Ammonites, can be found in Lyme Regis till today. |

It was Richard who started to supplemented his income by mining the coastal cliff-side fossil beds near the town, and selling his finds to tourists. He probably was the first fossil seller of Lyme Regis, who also used his cabinet-maker's tools to prepare the specimens to make them more attractive and salable. He taught his daughter and son how to look for and clean the fossils they found on the beach, by taking them iften on his fossil-hunting trips on the shore.

It was the time when paleontology was becoming recognised as a branch of the natural sciences and when fashionable for wealthy Georgians start to visit seaside towns to acquire fossils to add them to their cabinets of curiosities.

The French revolutionary wars and Napoleonic wars in the early 1800's caused wealthy British to avoid mainland Europe for vacations. Instead they travelled to seaside towns for holiday. These towns, such as Lyme Regis, became popular summer destinations.

On 19 August 1800, when Anning was 15 months old, she was taken to a travelling equestrian circus by a neighbour, Elizabeth Haskings, who was standing with two other women under an elm tree watching the show being put on by a travelling company of horsemen when lightning struck. Mary was the only survivor, being revived when placed in warm water. Anning's family said she had been a sickly baby before the event, but afterwards she seemed to blossom. Mary's remarkable survival instantly turned her into local celebrity. For years afterwards, members of her community would attribute the child's curiosity, intelligence and lively personality to the incident.Richard died in November 1810, of the combined effects of having fallen over a cliff on his way to Charmouth and of consumption, aged only 44. The death of Richard Anning left the family £120 (equivalent to approx. £12.000 today) in debt and the Annings, consisting of mother and two children, in financial crisis.

Shortly after her father's death, Mary Anning went down to the beach to look for the fossils and found and ammonite. On her way home, a lady in the street seeing the ammonite in her hand offered half-a-crown for it. Some researchers of Many Anning's life, believes, this fossil-sale was the moment when she fully determinate to go down to the beach again to look for more fossil and help her family to survive. Since than, Mary Anning spent her life unearthing "curios" from the fossil-rich cliffs near her home in Lyme Regis, Dorset, to sell to tourists and scientific collectors alike, and made many important discoveries. Her mother and brother, until he grew up and started to work as cabinetmaker, were astute collectors too and set up a table of curiosities near the coach stop at a local inn.

Anning's education was extremely limited, lasting only three or four years, where she learned to read and write. However, her reading and writing skills were above the average for the first half of the nineteenth century. These skills allowed her to correspond with many prominent scientists of her time in England and abroad.

Most of the important fossils discovered by Anning were studied and described by the following three men, who were to be in the vanguard of new interpretations of fossils and earth history.

| William Buckland (1784-1856) | William Daniel Conybeare (1787-1857) | Henry De la Beche (1796-1855) |

|

|

|

| Image credit: Wikipedia | Image credit: Wikipedia | Image credit: Wikipedia |

| William Buckland (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English

theologian who became Dean of Westminster.

He was also a geologist and

palaeontologist. Buckland wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named Megalosaurus. He pioneered the use of fossilised faeces in reconstructing ecosystems, coining the term coprolites. |

William Daniel Conybeare (7 June 1787 – 12 August 1857), dean of

Llandaff, was an English geologist,

palaeontologist

and clergyman.

He is probably best known for his ground-breaking work on fossils and

excavation in the 1820s, including important papers for the Geological

Society of London on

ichthyosaur anatomy

and the first published scientific description of a

plesiosaur.

|

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche (10 February 1796 – 13 April 1855) was an English geologist and palaeontologist, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who helped pioneer early geological survey methods. A great supporter of the work and importance of Mary Anning, of Lyme Regis, Henry De la Beche drew a sketch, in 1830, entitled Duria Antiquior, which shows reconstruction of prehistoric animals, based on fossils discovered by Mary Anning. |

Anning searched for fossils in the area's Blue Lias and Charmouth Mudstone cliffs, particularly during the winter months when landslides exposed new fossils that had to be collected quickly before they were lost to the sea.

With the years, Mary Anning became an fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who became known in England, Europe and North America for the discoveries she made. Anning's findings contributed to changes in scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the history of the Earth. Today, she is often referred as the "first women paleontologist" or "the first professional fossils-hunter".

Mary Anning's discoveries included the first correctly identified ichthyosaur skeleton when she was twelve years old; the first two nearly complete plesiosaur skeletons; the first pterosaur skeleton located outside Germany; and fish fossils were not known to the science before. Her observations played a key role in the discovery that coprolites, known as bezoar stones at the time, were fossilised faeces, and she also discovered that belemnite fossils contained fossilised ink sacs like those of modern cephalopods.

Between 7 and 12 July 1829 Mary left her hometown for the first in her live and made her first, and probably the only visit to London. She came on invitation of Charlote Murchison, wife of the prominent English geologist Roderick Murchison, while staying in their home. This fact shows she was threat by Murchisons as a friend and equal, not as working class trader.

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison (1792 – 1871) was a Scottish geologist who served

as director-general of the British Geological Survey from 1855 until his

death in 1871.

He is noted for investigating and describing the Silurian, Devonian and Permian

systems.

Charlotte Murchison became Roderick’s constant companion

during his travels, studies, and fieldwork, working alongside him.

On one such trip, specifically their voyage to the southern coast of England,

Charlotte went fossil-hunting with Mary Anning and the two became

close friends from then on.

Charlote collected fossils, some of which

she sent to James De Carle Sowerby,

to whom also Mary Anning was selling some of her fossil,

for inclusion in "Mineral Conchology of Great Britain".

One of the ammonites, she collected on

the Isle of Skye was named after her

by Sowerby - Ammonite murchisonae, which called

Ludwiga murchisonae today.

Mary Anning taught herself geology, anatomy, paleontology, and scientific illustration.

As a woman, she was treated as an outsider to the scientific community. At the time in Britain, women were not allowed to vote, hold public office, or attend university. The newly formed, but increasingly influential Geological Society of London did not allow women to become members or even to attend meetings as guests, until 1904. The only occupations generally open to working-class women were farm labour, domestic service, and work in the newly opened factories. Mary Anning's expertise and skills were however sought after by prominent figures, such as William Buckland and Henry de la Beche.

Mary Anning pioneering fossil hunter and palaeontologist stamps

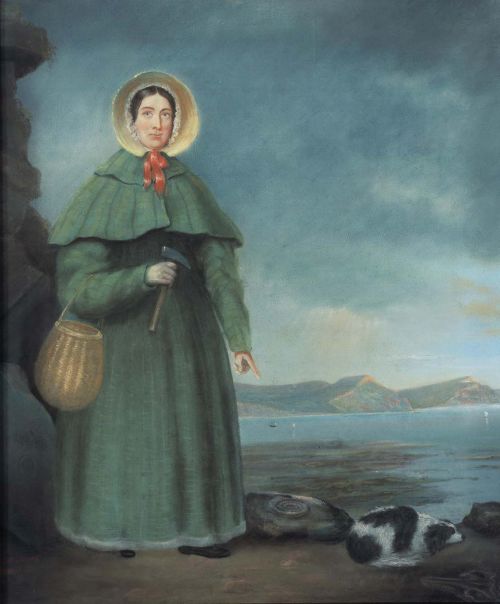

The first stamp on the Mini-Sheet is a reproduction of Mary Anning's portrait.

This stamp is only the third stamp depicted portrait of Mary Anning, two others, from the "undesired" category, were printed by Stamperija agency on behalf of Mozambique in 2012. According to MICHEL-online catalogue, in 2012, 829 stamps were printed by the Lithuania based agency on behalf of Mozambique, including many Paleontology related stamps: fossils, reconstructions of prehistoric animals, Charles Darwin and Mary Anning.

|

| The portrait of Mary Anning. Image credit: Wikipedia |

|

| The portrait of Mary Anning. Image credit: Wikipedia |

|

| Mary Anning on stamp of UK 2024, MiNr.: 5391, Scott: . |

The unsigned portrait, show Mary in her forties, painted in oil on board, was probably painted by William Gray in 1842 for the exhibition at the Royal Academy, but there no evidence it was shown on any exhibition of the Academy in that period. There are no documents about any connection between Gray who was based in London and Mary Anning, neither the reason for the paniting. Perhaps the painting became the property of Mary's brother Joseph Anning, after her death in 1847. It might suggests that the portrait may have been owned by Mary and probably was hanging in her shop or in her home.

After Joseph death in 1849, the painting passed to his widow, Amelia and through the family to her grand-daughter, Annete who presented it to the Natural History Museum in London in 1935.

Another, very similar portrait of Mary Anning, but in pastel, hangs in the foyer of the Geological Society at Burlington House on Piccadily in London, today.

This painting is signed by B. J. M. Donne and dated 1850, was painted three years after Mary's death. The portrait is a copy of Gray's one and probably was a commission by the donors of the Anning memorial window in St. Michael's Church.

It was drawn when the artist Benjamin Donne was 19 years of age.

Donne’s school was close by to Anning’s fossil shop in Lyme Regis and he knew her quite well. Most likely Donne have been given access to the earlier portrait of Mary by the widow of Josep, Amelia Anning.

This portrait was presented to the Geological Society in 1875 by William Willoughby Cole, the 3rd Earl of Enniskillen (1807–1886), and a Fellow of the Society.

Donne's painting is clearer and brighter and have some differences from the original: Mary appears slimmer and less stocky, the skull of an ichthyosaur became shorter and wider, and few new elements were added:

- An Ammonite on a block of rock was added between Mary and her dog.

- Another, small, Ammonite was added in the rock behind Anning, just below her basket.

- Three small ships were added on the sea.

- The foreshore rock ledges, where many specimens were collected by Mary, added behind her.

- In the background Thorncombe Beacon hill was added next to the Golden Cap.

|

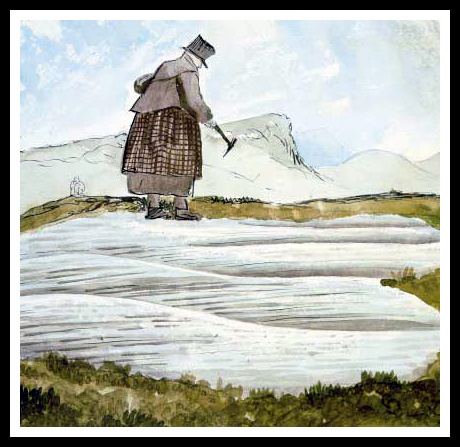

| The watercolour of William Buckland often mistaken with Mary Anning. Image credit: Wikimedia commons |

Another watercolour portrait, shows a top-hatted figure with collecting bag and hammer in the field and has been considered to be by Lyme Regis fossil collector.

Many articles consider it shows Mary Anning from the back and was painted by a friend of Mary Anning, who later became the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain Henry De la Beche.

However, several researchers of Mary Anning's life, including Tom Sharpe, concluded that the image shows not Anning, but most likely the Oxford geologist William Buckland, and that the artist was not Henry De la Beche, but the surveyor Thomas Sopwith.

It was probably painted when Sopwith accompanied Buckland on a tour of North Wales in October 1841. The foreground features are Sopwith’s rendering of ice-smoothed and glacially-striated bedrock and not the foreshore rocks or mudflows of the Dorset coast.

The watercolour was probably drawn in the mountains of Snowdonia, perhaps either at the head of the glacial trough of Nant Francon or on the western side of Snowdon.

For details about this painting, please read "A case of mistaken identity: is Mary Anning (1799–1847) actually William Buckland (1784–1856)?", by Tom Sharpe (doi: 10.17704/1944-6187-40.1.68).

The second stamp on the Mini-Sheets shows fossil of Ichthyosaur communis/anningae

|

|

| Ichthyosaurus communis/anningae on postage stamp pf Royal Mail 2024, MiNr.: 5392, Scott: . | The fossil of Ichthyosaurus communis/anningae in collection of the Natural History Museum in London. Image credit: NHM UK. |

|

| The first articulated skeleton of a Jurassic ichthyosaur. discovered by Joseph and Mary Anning in 1811-1812. Image credit: fossilguy.com |

Fisrt, in 1811, Joseph found the skull, then nearly 12 months later, Mary found the torso of the same animal.

The fossil discovered by Joseph and Mary Anning was not the first fossil of ichthyosaur collected in England, but was the first fossil brought to scientific attention, recognized as remains of a new animal and it was the first ever scientific description of an ichthyosaur.

Many museums across England had, fossils of Ichthyosaurs, but were misinterpreted and assigned to crocodiles, fish, lizard or as "sea-dragons".

The "Ichthyosaurus" name ("fish lizards") was first time used by Charles Koenig (König), curator of the Department of Natural History British Museum, in 1817, to describe another fossil of the prehistoric animal. This fossil was not the skull and torso discovered by Josep and Mary Anning nor any other ichthyosaur fossil found by Mary Anning.

Since 1812, Mary Anning found many ichthyosaur skeletons, single bones and coprolites of these prehistoric marine animals, which were purchased by many museums in Britain and overseas. The fossil shown on the stamp is not the first ichthyosaur skeleton discovered by Annings, but ichthyosaur with the coprolite within its ribcage, purchased from Mary Anning by the British Museum in 1835, as written on the micro-text of the Mini-Sheet.Discovery of coprolite (fossilized feces) within a fossil, was an important evidence the ichthyosaur was once lived animal, as only living organisms produce feces, after their eat something.

Perhaps, this is the reason the Natural History Museum in London provided the photo of ichthyosaurus with the coprolite within its ribcage, rather than the skull of the fist discoved ichthyosaurus, by Mary and Joseph Anning, to the Chase agency to reproduce it on the stamp.

In 2015 the specimen, shown on the stamp, was renamed by Dr. Dean R. Lomax and Dr, Judy A. Massare from Ichthyosaurus communis to Ichthyosaurus anningae in honour of Mary Anning, as they recognized some differences of this specimen from Ichthyosaurus communis species.

Ichthyosaurs ("fish lizards") are an extinct group of aquatic marine reptiles (not fish nor lizards), who belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria.

Ichthyosaurs, lived in the Mesozoic era from the Early Triassic to the Late Cretaceous, about 250 million to 90 million years ago and were contemporaries of the Dinosaurs. However, they died out about 30 million years before the extinction of Dinosaurs.

The ichthyosaurs through convergent evolution evolved a fish-like body adapted for living in water exclusively. By the end of the Triassic, ichthyosaurs had adapted to fully aquatic conditions with treamlined bodies, fins, and a sickle-shaped tail. The fins and tail were used to propel the animals through the water when swimming. They were unable to return to land – and hence were unable to lay eggs on land like modern sea turtles do today.

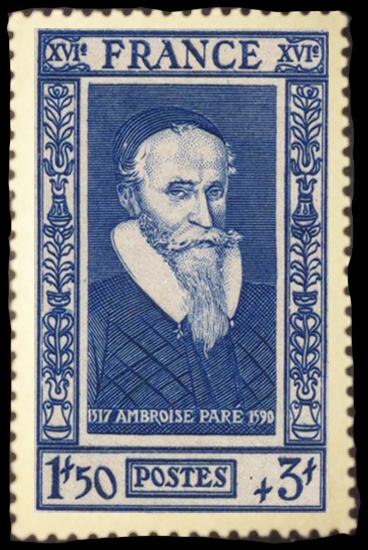

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith or "dung stone") is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology.

They serve a valuable purpose in paleontology, because they provide direct evidence of the predation and diet of extinct organisms. Coprolites may range in size from a few millimetres to over 60 centimetres.

When coprolites were first discovered, they were identified as fossilized fir tree cones or bezoar stones.

Bezoar stones were undigested masses found trapped in the gastrointestinal system, and were once

believed to have magical properties, capable of neutralizing any poison.

This claim was put to the test by French surgeon Ambroise Pare.

In 1567, a cook at Pare's court was caught stealing fine silver cutlery,

and was condemned to be hanged.

The cook agreed to be poisoned instead, on the condition that he would be

given a bezoar straight after the poison and go free in case he survived.

The stone did not cure him, and he died in agony seven hours after being poisoned.

Thus Pare had proved that bezoars could not cure all poisons.

Anning’s attention was drawn to these objects, as she usually discovered them within the ribs or near the pelvis of the ichthyosaur fossils. She also noticed that, when the coprolites were broken open, they sometimes contained fossilized fish bones, scales, and the bones of smaller ichthyosaurs. Mary herself believed them to be fossilized feces.

In his article "On the Discovery of Coprolites, or Fossil Fæces, in the Lias at Lyme Regis, and in other Formations" published in Transactions of the Geological Society in 1829, Buckland gave credit to Mary Anning and mentioned her opinion about this type of fossils.

It has long been known to the collectors of fossils at Lyme Regis, that among the many curious remains in the lias of that shore, there are numerous bodies which have been called Bezoar stones, from their external resemblance to the concretions in the gall-bladder of the Bezoar goat, once so celebrated in medicin. ...

The certainty of the origin I am now assigning to these Coprolites, is established by their frequent presence in the abdominal region of the numerous small skeletons of Ichthyosauri, which, together with many large skeletons of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri, have been found in the cliffs at Lyme, and supplied to various collectors by the skill and industry of Miss Mary Anning. I have two of these skeletons, in each of which the Coprolites are very apparent, but flattened; and Miss Anning informs me that since her attention has been directed to these bodies, she has found them within the ribs or near the pelvis of almost every perfect skeleton of Ichthyosaurus which she has discovered. She further informs me, that whereas in the entire thickness of the lias formation there are certain strata that abound in bones, whilst in others they are comparatively rare; so also the so-called Bezoars are most abundant in those parts of the formation in which the bones of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri are most numerous. I propose to assign the name of lchthyosauro-coprus to the fossil freces which are thus evidently derived from Ichthyosauri.

In variety of size and external form the Coprolites at Lyme Regis resemble oblong pebbles or kidney-potatoes. They, for the most part, vary from two to four inches in length, and from one to two inches in diameter. ...

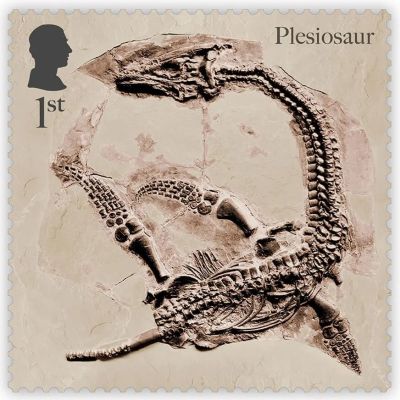

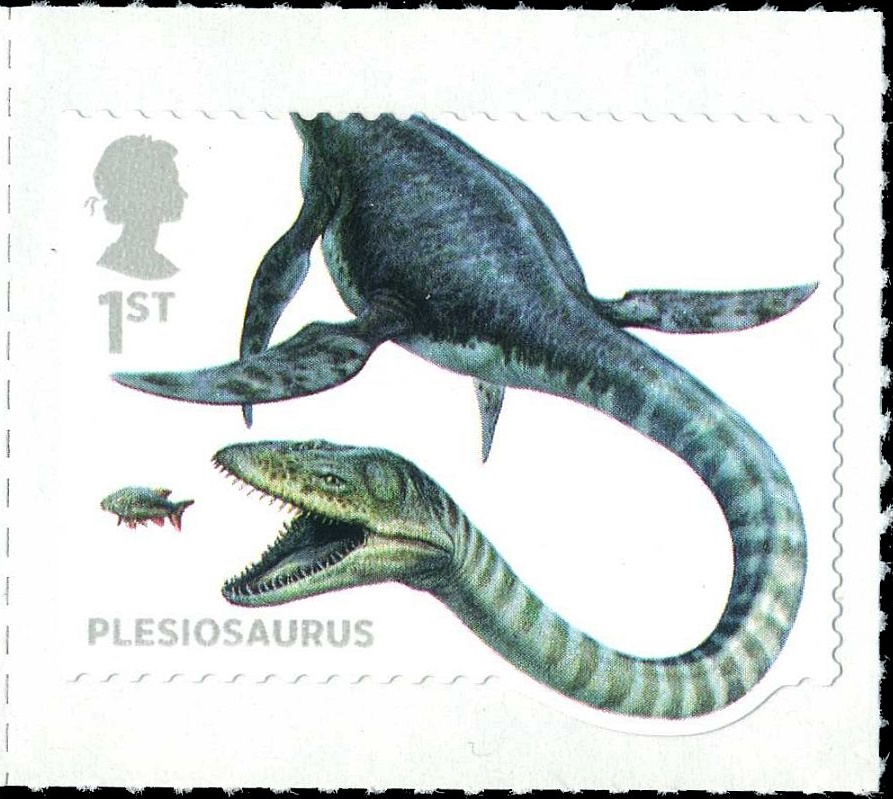

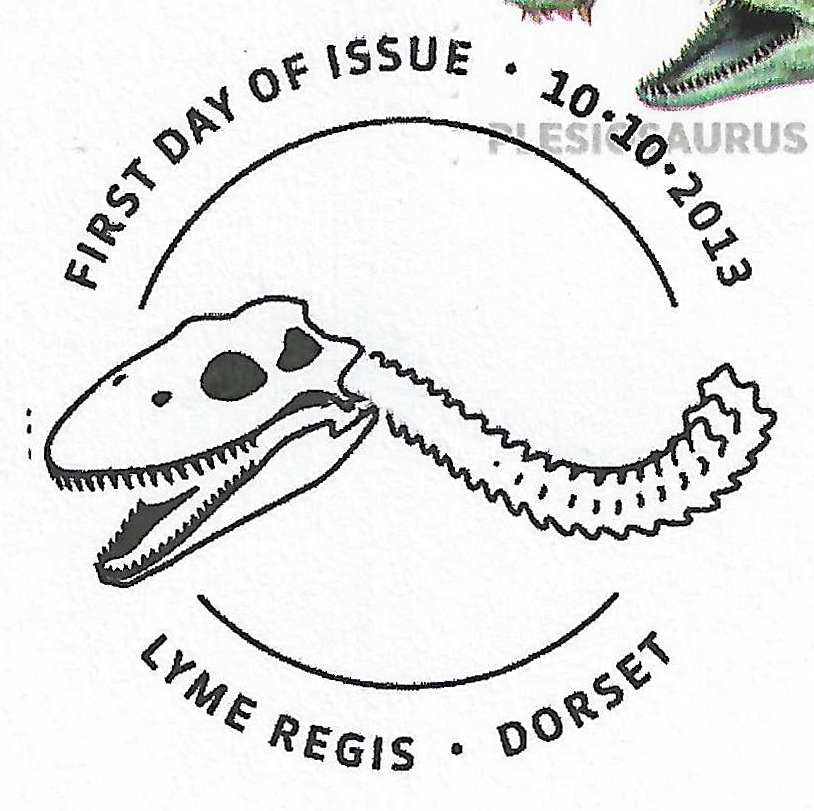

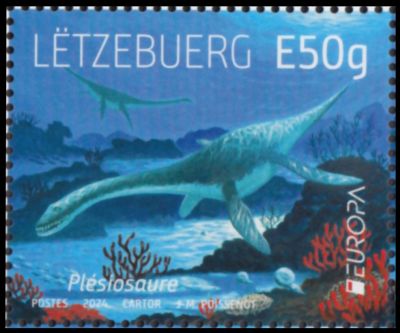

The third stamp on the Mini-Sheets shows fossil of Plesiosaurus macrocephalus

The fossil, of near-complete fossilized juvenile skeleton of the marine reptile lacking part of the tail, was collected by Mary Anning in 1823 at Lyme Regis, Dorset. The fossil age was estimated 201-195 million years ago and has a total length of 1.5 meter. |

| Fossil of Plesiosaur on stamp of UK 2024, MiNr.: 5394, Scott: . |

|

|

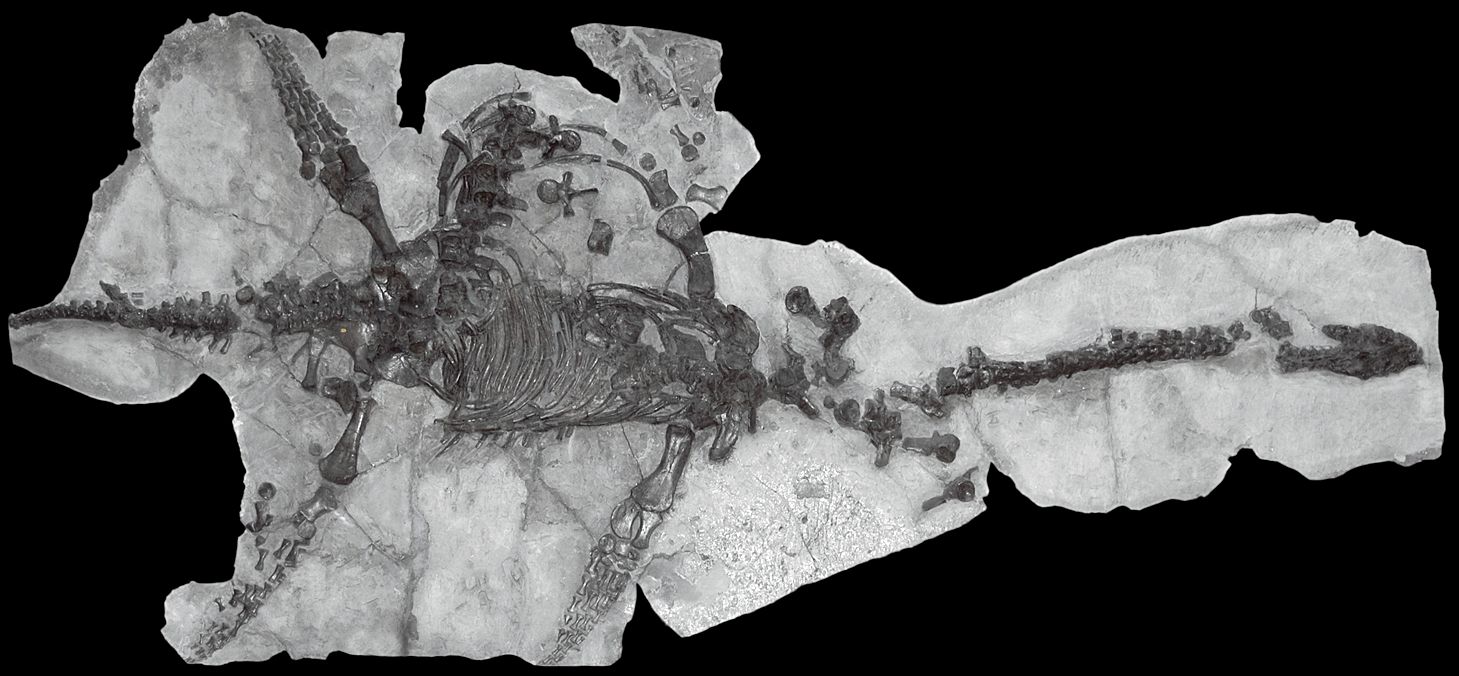

| Reconstruction of Plesiosaurus on stamp of UK 2013, MiNr.: 3535, Scott: 3237, and First-Day-of-Issue Postmark. |

|

| Reconstruction of Plesiosaurus in its living environment on stamp of Luxembourg 2024, MiNr.: 2369, Scott: . |

The Plesiosaurus on the stamp belongs to another, not less spectacular, species: Plesiosaurus macrocephalus, discovered by Mary Anning in 1830.

In her letter to William Buckland Mary Anning wrote:

I write to inform you that in the last week I discovered a young Plesiosaur ... it is without exception the most beautiful fossil I have ever seen. The tail an one paddle is wanting (which I hope to get at the first rough sea) every bone is in place, in short if it had been made of wax it could not be more beautiful, but I should remark that the head it twice large in proportion as those I have hiherto found. The neck has most graceful cure and what make it more interesting is that resting on the bone of pelvis, its coprolite finely illustrated.

The presence of coprolite withinh the pelvic region made this a remarkable find.

The Plesiosaur was named by William Buckland in 1836, who credited Mary Anning for the discovery, and later described by Richard Owen in 1840.

William Willoughby, Lord Cole, later Earl of Enniskillen (and Fellow of the Geological Society), purchased the fossil in 1831 for the then massive sum of 200 guineas.

It was subsequently acquired from him by the Natural History Museum, London, where it has remained on display in the museum’s ‘Fossil Marine Reptiles’ hall.

Plesiosaurus macrocephalus certainly does not belong to the long-necked, small-skulled genus Plesiosaurus. It is probably a juvenile rhomaleosaurid but has not yet been assigned to a new or existing genus. So, pending revision of the taxon and referral to a different or other existing genus, it is still named Plesiosaurus, following Owen.

Plesiosaurus ("near lizard") is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic.

The genus was so-named by William Conybeare and Henry De la Beche, to indicate that it was more like a normal reptile than Ichthyosaurus, which had been found in the same rock strata just a few years earlier. Conybeare and De la Beche coined the name for partial skeleton from the Bristol region, Dorset, and Lyme Regis in 1821, from the collection of Colonel Thomas James Birch.

Retired officer in the Life Guards, Liuetenant-Colonel Thomas James Birch

(1768-1829), was geologist, fossil collector and early friend of Gideon Mantell.

He lived in Lincolnshire, but collected fossils over much of Britain.

The Colonel purchased many specimens from Mary Anning, which he auctioned in 1820

for the benefit of her family, as they ran in the financial problems, once again.

In his letter to Mantell Birch wrote:

... I am going to sell my collection for te benefit of the poor women

[mother of Mary, Molly Anning] and her son [Joseph] and daugther [Mary]

at Lyme who have in truth found almost all fine things, which have benn

submitted to scientific investigation: when I went to Charmouth and Lyme

last summer I found these people in considerable difficulty - on the act of

selling their furniture to pay their rent - in consequence of their not having

found one good fossil for near a twelve month.

It is unknown if the Plesiosaurus skeleton in collection of Colonel Birch was discovered and unearthed by himself or he purchased it from Many Anning or another fossil hunter.

Plesiosaurus is distinguishable by its small head, long and slender neck, broad turtle-like body, a short tail, and two pairs of large, elongated paddles.

Plesiosaurus fed mainly on clams and snails, and is thought to have eaten belemnites, fish and other prey as well.

According to recent research, the neck of Plesiosaurus wasn't that flexible. Plesiosaurus were able to move their neck left-right and a bit up and down, but was unable to bend it like a swan, as shown in the Royal Mail stamp and postmark in 2013.

Its neck could have been used as a rudder when navigating during a chase. The animal may have fed by swinging its head from side to side through schools of fish, capturing prey by using the long sharp teeth present in the jaws.

Its U-shaped jaw and sharp teeth would have been like a fish trap. It swam by flapping its fins in the water, much as sea lions do today, in a modified style of underwater “flight.”

Plesiosaurus gave live birth to live young in the water like sea snakes. The young might have lived in estuaries before moving out into the open ocean.

The first complete skeleton of Plesiosaurus was discovered by Mary Anning in Sinemurian (Early Jurassic)-age rocks of the lower Lias Group in December 1823, two years after Henry De la Beche and William Conybeare named the genus.

Initially, Mary didn't recognised the skeleton belong to Plesiosaurus, only when she started remove the rock surrounding the bones did it become clear what she found.

The skeleton was about 3 meters long and 1.2 meters wide, its head was very small in relation to its body - 20 cm about. It most remarkable feature was the neck, as it was longer as the rest of the body. Due to its much better condition, the skeleton discovered by Anning became the holotype, instead of the fossil used for the genus description in 1821.

It was of a strange 2.7 meters long animal with a small head, only 10 - 12 cm long like a turtle's but an inordinately long neck, which De la Beche at least thought must have been an adaptation for lakes and rivers not the sea.

The animal was described to the largest audience yet at a Geological Society meeting on 20 February 1824, a read letter day for British palaeontology. The skeleton was acquired by the Duke of Buckingham, who made it available to the geologist William Buckland. He in turn let it be described by Conybeare on 24 February 1824 in a lecture to the Geological Society of London, during the same meeting in which for the first time a dinosaur was named, Megalosaurus, by Buckland in his famous paper the "Notice on the Megalosaurus or great fossil lizard of Stonesfiel".

Conybeare recognized that the specimen was a virtually complete example of the little-known Plesiosaurus.

In the "Geology and Mineralogy Considered with Reference to Natural Theology", 2 vols., published in London in 1836" William Buckland described it:

The discovery of this genus forms one of the most important additions

that Geology has made to comparative anatomy.

It is of the Plesiosaurus that Cuvier asserts the structure

to have been ... altogether the most monstrous, that have been yet found

amid the ruins of a former world.

To the head of a Lizard, it united the teeth of a Crocodile; a neck of

enormous length, resembling

the body of a Serpent; a trunk and tail having the proportions of an

ordinary quadruped, the ribs of a Chameleon, and the paddles of a Whale.

In 1848, the skeleton was bought by the British Museum of Natural History and catalogued as specimen NHMUK OR 22656 (formerly BMNH 22656). The skeleton was assigned to Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus. This skeleton provided clarity on the anatomy of Plesiosaurus, and showed that the animal had a long neck. Unequivocal specimens of Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus are limited to the Lyme Regis area of Dorset.

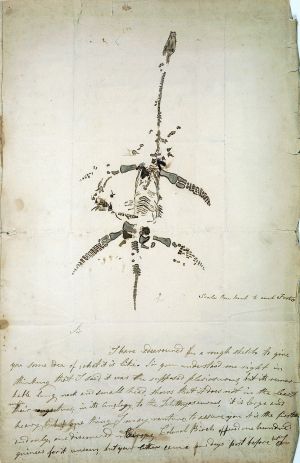

The first complete skeleton of Plesiosaurus discovered by Mary Anning in 1823.

|

| Drawing of complete Plesiosaurus skeleton recovered by the Annings in 1823. Image credit: Wikipedia |

|

| Georges Cuvier on commemorative postmark of France 2019 |

When in March 1824, Cuvier received the sketch of the fossil, he thought that it might be forgery, a composite of two different animals either deliberated or mistakenly combined into one skeleton by Mary Anning. He wrote to Conybeare suggesting he check it.

When more detailed drawings of the specimen, created by Mary Anning, was forwarded by Conybeare and Buckland to Cuvier, he recognized it as a genuine. Since than, the scientific community began to recognize the paleontological value of the fossils recovered by Mary Anning (young women from the labour class, at that time 25 years old only) and her family.

As result of the impression made by the fossil of the unusual animal, Cuvier held Anning in high regard, and mentioned her by name in his book "Recherces sur les ossemens fossiles", publushed in Paris in the same year (1824).

In May 1824, Cuvier sent the French geologist Constant Prevos to England with the mission to purchase some specimens of the new marine reptiles for the Natural History Museum in Paris.

In June 1824, Prevot accompanied by famous British geologist Charles Lyell, arrived Lyme to see Mary Anning and visited their fossil store.

|

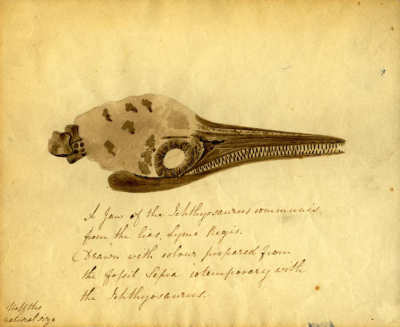

| The sketch of an ichthyosaur, ainted with fossil belemnite ink. Image credit: Fossil Guy |

In 1826 Anning discovered what appeared to be a chamber containing

dried ink inside a belemnite fossil.

She showed it to her friend and artist Elizabeth Philpot who was able

to revivify the ink and use it to illustrate some of her own ichthyosaur fossils.

Soon other local artists were doing the same, as more such fossilised ink

chambers were discovered.

Anning noted how closely the fossilised chambers resembled the ink sacs of

modern squid and cuttlefish, which she had dissected to understand the anatomy

of fossil cephalopods, and this led William Buckland to publish the conclusion

that Jurassic belemnites had used ink for defence just as many modern cephalopods do.

Elizabeth Philpot and her two other fossil collecting sisters had a close-knit friendship with Mary Anning. A collection of her letters is housed at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

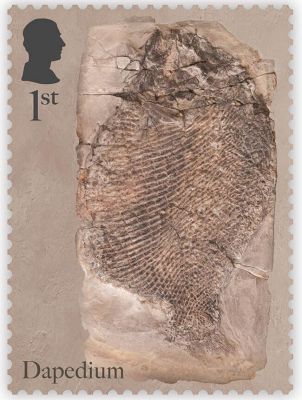

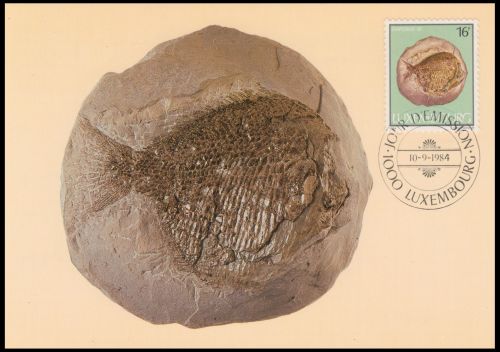

The fourth stamp on the Mini-Sheets shows fossil of Jurassic fish Dapedium politum

The fossil, of near-complete Jurassic fish fossil showing scale pattering and delicate fin structure collected by Mary Anning in 1829 at Lyme Regis, Dorset. The fossil age was estimated 199-190 million years ago and has a total length of 33 cm. Even though this Dapedium fossil was well preserved example, it was not a new species. |

|

| Fossil of Jurassic fish Dapedium politum on stamp of UK 2024, MiNr.: 5393, Scott: . | Fossil of Jurassic fish Dapedium on Maxi Card of Luxembourg 1984. The stamp is a part of the set of four stamps "Fossils of Luxembourg". |

Dapedium is an extinct genus of primitive neopterygian ray-finned fish, who lived mostly in the Jurassic seas of Europe, a peripheral continental shelf sea of the Tethys Ocean. The various species of Dapedium ranged from 9 to 40 centimetres long, and all had an oval to near-circular body. The skin was covered with thick, rhomboid, ganoid (enamel-like) scales.

Armor around the head helped avoid blunt attacks from some enemies, and scales with barbs could discourage larger predators.

The tail was short and stout, providing the power for a sudden change in direction while the fish was swimming. Dapedium developed its circular-shaped body as it matured.

When young, it was long and thin, like most other prehistoric fish. This would have helped it swim faster to escape predators until it developed its defences.

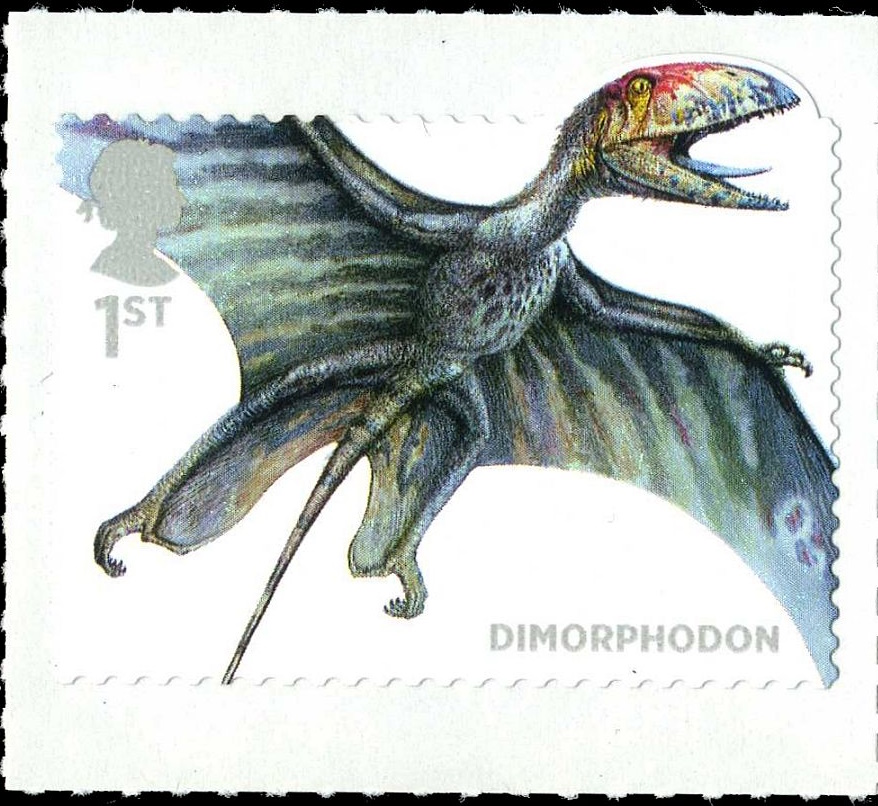

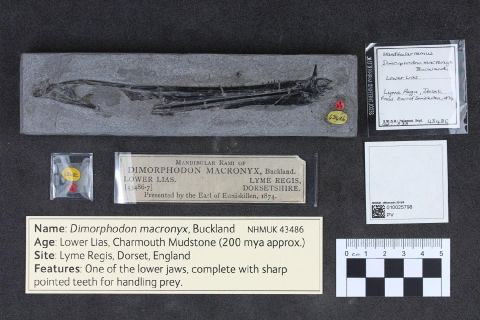

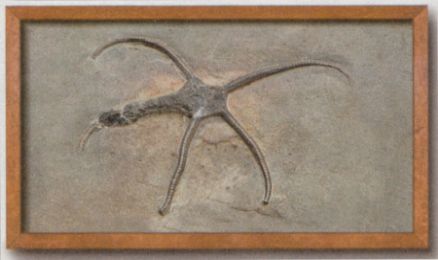

Fossils of another three prehistoric animals depicted on the selvages of the Mini-Sheet: a pterosaur Dimorphodon macronyx, an Ammonites greenoughi and a bittle star Palaecoma egertoni.

The jaw of a pterosaur Dimorphodon macronyx.

|

| The jaw of a pterosaur Dimorphodon macronyx from collection of the Natural History Museum in London, the specimen number NHMUK 43486. |

|

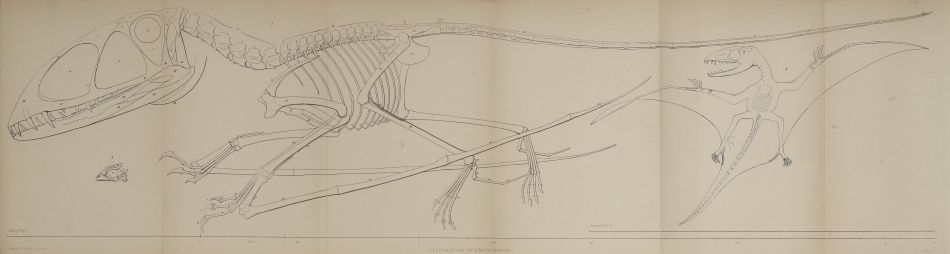

| The first pterosaur skeleton discovered by Mary Anning and described by William Buckland in 1829 as Pterodactylus macronyx. Image credit: Data Portal of NHM UK: PV R 1034, |

|

| The first skeleton of Pterodactylus, described by Cosimo Alessandro Collini in 1784. Image credit: Wikipedia |

|

| Fossil of Pterodactylus on meter frankings of Solnhofen community of Germany. |

|

| Dimorphodon reconstruction on postage stamp of Royal Mail 2013, MiNr.: 3527, Scott: 3229. |

A small fragment of jaw was found by the Philpot sisters, friends of Mary. It was later acquired by Oxford University where it became the specimen number "OUM J 28251".

Previously pterosaur bones had been found but not recognised in England, possibly as early as 1757 when some fossil "bird" bones were mentioned from the Jurassic Stonesfield "slate" of Oxfordshire. Prior to Anning's discovery, fossils of hollow bone fragments found in Britain were presumed to have been the remains of ancient birds.

At the time, the Anning's fossil was found, fossils of all flying reptiles were assigned to Pterodactylus.

The animal known as Pterodactylus today,

was first time described, but not named, by Italian naturalist

Cosimo Alessandro Collini in 1784, based on a fossil skeleton

that had been unearthed from the Solnhofen limestone of Bavaria (now Germany,

the same place where the first skeleton of iconic fossil,

Archaeopteryx will be found almost 80

years later).

Collini did not conclude that it was a flying animal, but thought it

might be a sea creature.

It was the prominent French naturalist Georges Cuvier, who in 1800, recognized the animal

(based on the same fossil) as reptile, but named as Ptéro-Dactyle in 1809, and proposed

it was the flying reptile:

"It is not possible to doubt that the long finger served to support a membrane that,

by lengthening the anterior extremity of this animal, formed a good wing."

As was the case with most early pterosaur finds, Buckland classified the remains in the genus Pterodactylus, coining the new species Pterodactylus macronyx. The specific name is derived from Greek makros, "large" and onyx, "claw", in reference to the large claws of the hand.

In the same blue lias formation at Lyme Regis, in which so many specimens

of Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus have been discovered by Miss Mary Anning,

she has recently found the skeleton of an unknown species of that

most rare and curious of all reptiles, the Pterodactyle, an extinct genus, which

has yet been recognized only in the upper Jura limestone beds of Aichstedt

and Solenhofen, in the lithographic stone, which is nearly coeval with the chalk of England.

In size and general form and in the disposition and character of its wing's,

this fossil genus, according to Cuvier, somewhat resembled our modern bats

and vampires, but had its beak elongated like the bill of a woodcock, and

armed with teeth like the snout of a crocodile; its vertebra, ribs, pelvis, legs,

and feet, resembled those of a lizard; its three anterior fingers terminated in

long hooked claws like that on the fore-finger of the bat; and over its body was

a covering, neither composed of feathers as in the bird, nor of hair as in the

bat, but of scaly armour like that of an Iguana; —in short, a monster resembling

nothing that has ever been seen or heard-of upon earth, excepting the

dragons of romance and heraldry.

Moreover, it was probably noctivagous and insectivorous, and in both these points

resembled the bat; but differed from it, in having the most important bones in its

body constructed after the manner of those of reptiles.

With flocks of such-like creatures flying in the air, and shoals of no less monstrous

Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri swarming in the ocean, and gigantic crocodiles and tortoises

crawling on the shores of the primeval lakes and rivers, —air, sea, and лand must have been

strangely tenanted in these early periods of our infant world.

As the most obvious point of difference between our new species of Pterodactyle

and those described by Cuvier, consists in the greater length of the

claws, I propose to designate it by the name of Pterodactylus macronyx ...

The individual we possess must have been nearly of the size of a raven:

the head is wanting, but much of the skeleton, though dislocated, is nearly

entire ; part of the neck is also lost...

These three fingers, terminating in claws so long

that I have chosen them to characterize the species by the name macronyx,

must have formed a powerful paw, wherewith the animal was enabled to

creep, or climb, or suspend itself from trees...

In the 1850s, another pterosaur specimen, this time with a skull was found at Lyme and also purchased by the British Museum, probably around 1858 – it is specimen number NHMUK R1035, followed by another skull in 1868 and also bought by the British Museum (specimen number NHMUK 41212-13). Sadly, Buckland never got to see the new material, as he passed away in 1856, and so these new specimens were described by Richard Owen.

|

| Image credit: Data Portal of NHM UK. |

The two different sizes of teeth in the jaws of dimorphodon suggest that this flying dinosaur was a fish-eater. It had a large, puffin-like beak, short wings and a long tail. Dimorphodon represents the older rhamphorhynchoid pterosaurs.

The lower jaws (mandibular rami) of Dimorphodon macronyx depicted on the Mini-Sheet, is one of the lower jaws, complete with sharp pointed teeth for handling prey. The jaw was discovered in Lower Lias, Charmouth Mudtsone layer an was dated 200 million years old. The jaw was presented to the British Museum by the Earl of Enniskillen in 1874, has the specimen number NHMUK 43486.

According to "Appendix. A Catalogue of Fossil Specimens Collected by Mary Anning (1799–1847) Held in the Collections at the Natural History Museum, London" compiled by the former Keeper of Palaeontology and curator of fossil reptiles Sandra D. Chapman and Angela C. Milner, published in 2010, this jaw was purchased from Mary Anning, either directly or as part of collections of others whom Mary sold her fossils. Unfortunately, there are no further details, when and where the jaw was collected.

Reconstruction of Dimorphodon macronyx by Richard Owen from 'Monograph of the Fossil Reptilia of the Liassic Formations’, Monograph of the Palaeontographical Society, Vol 35 (1881).

Mary Anning, usually, associated with her discoveries of marine vertebrate fossils and the pterosaur, but she also made significant finds of invertebrate, like crustaceans and starfish, as well as crinoids.

|

| One of ammonites (Ammonites greenoughi) discovered by Mary Anning in Lyme Regis. |

This ammonite is abbubdant in Lias layers of England, especially at Lyme Regis, Bath and Yorkshire, as well as in France, Germany and Switzerland. The ammonite depicted by the Royal Mail has been half-sectioned and was collected by Mary Anning in Lyme Regis in 1838. It was donated to the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society by Mr. Blake in 1935 and received the specimen number "TTNCM 8517". It is about 77mm in width and 66mm height.

Ammonites greenoughi was named by James Sowerby (1757-1822) in 1816. James Sowerby, who named the ammonite, was an English naturalist, illustrator and mineralogist. One of his projects was the "Mineral Conchology of Great Britain", a comprehensive catalogue of many invertebrate fossils found in England, was published over a 34-year time-span, the latter parts by his sons James De Carle Sowerby and George Brettingham Sowerby I. Many notable geologists and other scientists of the day were to lend or donate specimens to his collection. The finished work contains 650 coloured plates distributed over 7 volumes.

|

| Since the first Ammonite stamp was issued in Algeria in 1952, many countries in the world featured these cephalopods on their stamps and postmarks as shown on the philatelic exhibit of Mr. Rudolf Hofer from Switzerland. |

|

|

"Nautilids and Ammonites worldwide - the world of Cephalopods and their reflection in Philately", by Hans Ulrich Ernst, Christian Klug. Published in 2011. Preview of some pages is here Amazon: UK, DE |

|

| Another Ammonite, probably Androgynoceras was depicted on one of the First-Day-of-Issue Postmark, designed by the Royal Mail. |

The attenuated and ramifying sutures

of the septa are remarkably striking in the present specimen,

and put me in mind of the friendly and attentive

Geologist, Greenough, whose genius spreads and ramifies

so abundantly, that I could not resist commemorating it

with sentiments of friendship, that the suavity

of his manners has stamped on my mind.

May he continue long to enjoy that ardour, which contributes so

much to his happiness, and is so instructive to all around

him.

George Bellas Greenough is best-known for his Geological Map

of England and Wales, published

in 1820, which used new data and an innovative colouring system to highlight

deposits of different types of rocks and minerals.

These maps were ground-breaking in the way that they displayed the minerals

and resources that were lying under the ground.

This was an exciting development not only for those with an interest in

geology or the study of fossils, but also to those who stood to benefit

financially.

George Greenough received assistance in the collection of his geological

facts from William Buckland, Reverend William Daniel Conybeare,

Henry Thomas De la Beche and many other members of the Geological Society

of London.

Greenough later became a controversial figure due to his clashes with

William Smith, another geologist who had also made a very similar geological

map at almost exactly the same time and who credited with creating the

first detailed, nationwide geological map of any country.

Today William Smith is often called as the "Father of English Geology".

Unlike Smith, Greenough did not go into the field and study the geology

first hand.

Instead he relied on others sending him information which he would then

collate.

While Smith had relied on a theory about the linear arrangement of strata

identified by characteristic fossils to extrapolate from his observations

and so was able to map out the distribution of strata across the country,

Greenough has doubts of the usefulness of fossils in correlating strata.

Greenough considered that fossils had been very overrated in their usefulness,

as fossil species were different from modern species, so fossils could not

be used to 'theorise' about or deduce the relative age and the conditions

of deposition of the rocks.

Indeed, he was suspicious of the concepts of 'stratum' and 'formation',

much used by Smith.

For this reason Greenough wanted to dissociate himself and the

Geological Society map from the man who was using fossils to identify strata.

This did not, however, stop Greenough from using Smith's map as a source

of material for the Geological Society's version of the map and there is

debate about how much Smith's map influenced Greenough.

Both maps now hang side by side on the main staircase in the entrance

hall of The Geological Society apartments in Burlington House, London.

Today the ammonite species called Charmasseiceras greenougi. It was reassigned to another, better described species, because Sowerby didn't mentioned, in his description, where and in what strata the specimens was collected. Note1

Ammonites greenoughi discovered by Mary Anning wasn't the new or ground-breaking species, as ichthyosaur, plesiosaur or pterosaur, but was one of many ammonites she collected on the shore of Lyme Regis.

An ammonite was the first fossil Mary found and sold by herself in 1810, at the age of 11, shortly after the death of her father. The ammonites were, and still are, the most abundant fossils at the Lyme shore.

In August 1837, Prusian (today Germany) naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt, the feature explorer of Australia,who visited Lyme Regis recorded in his letter:

We saw the dark wall of the Lias against which the sea beats daily, dislodging the vestiges of the primeval world. We walked over thousands of ammonites embedded in the smooth-washed, slippery paste of the Lias along the shore. And we had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of paleontology, Mary Anning.

The sale of small fossils such as ammonites, belemnites, bivalves, crinoids and single reptile's vertebrate, was the daily business of Anning's family, who sold it in big numbers to Lymes' visitors. The best species were sold to museums, but very few of such small purchases were recorded.

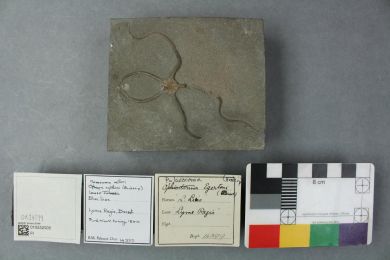

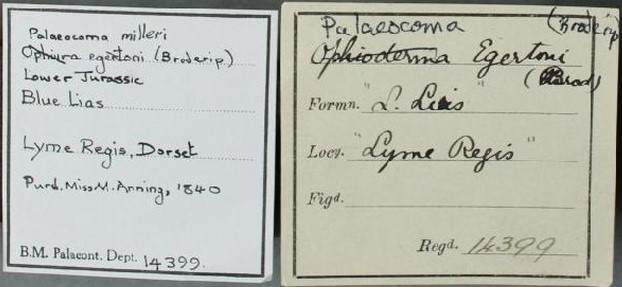

Three fossilized bittle star, Palaecoma milleri (originaly named Ophiura egertoni ) were collected by Mary Anning and purchased from her by the British Museum in 1840. It was the first time Mary Anning's name was formally recorded as a collector of a specimen acquired by a museum. The British Museum recorded in the museum's catalogue: "Species of Ophiura on blue lias Lyme Regis Bougth of Miss M. Anning".

|

|

| One of the bittle stars, Ophiura egertoni, purchased from Mary Anning by the British Museum in 1840, specimen number: PI OR 14399. Images credit: Data Portal of NHM UK. |

The labels attached to one of the bittle starspurchased from Mary Anning

by the British Museum in 1840. |

Ophiura egertoni was described by William John Broderip in 1835, based on the fossil discovered by Sir Philip de Malpas Grey Egerton (an English palaeontologist and Conservative politician) at Bridport about 12 km east of Lyme.

|

| One of the bittle stars, Ophiura egertoni, depicted by the Royal Mail. |

William John Broderip FRS (21 November 1789 – 27 February 1859) was an English lawyer and naturalist. To the Transactions of the Geological Society Broderip contributed numerous papers, including "Description of some Fossil Crustacea and Radiata, found at Lyme Regis, in Dorsetshire", which was published in Transaction of the Geological Society of London in 1835, where he desribed the bittle star.

By later review, Ophiura egertoni species was moved to Palaeocoma genus and renamed to Palaecoma egertoni, but later on, the species was reassigned to Palaecoma milleri.

Brittle stars are echinoderms in the class Ophiuroidea, closely related to starfish,

who, usually, live in deep water.

They crawl across the sea floor using their flexible arms for locomotion.

The ophiuroids generally have five long, slender, whip-like arms which may reach up

to 60 cm in length on the largest specimens.

Their arms often forked and spiny—are distinctly set off from the small disk-shaped body.

The arms readily break off but soon regrow/regenerated.

The animal feeds by extending one or more arms into the water or over the mud, the other arms serving as anchors.

It is interacting, that no one of the famous British naturalist (some of them were even friends of Anning and supported her financially), named any new species in honour of it discoverer. The only fossil named after her during her lifetime was the Acrodus anningiae and Belenostomus anningiae a fossil fish species named by the Swiss American naturalist, Louis Agassiz in 1841 and 1844 accordantly.

The Karroo reptile genus Anningia was named much later in 1927 by the South African paleontologist Robert Broom (1866-1951). In 1932 this taxon was made the basis for a new order, the Anningiamorpha, by Broom too.

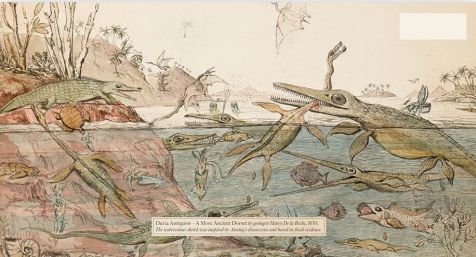

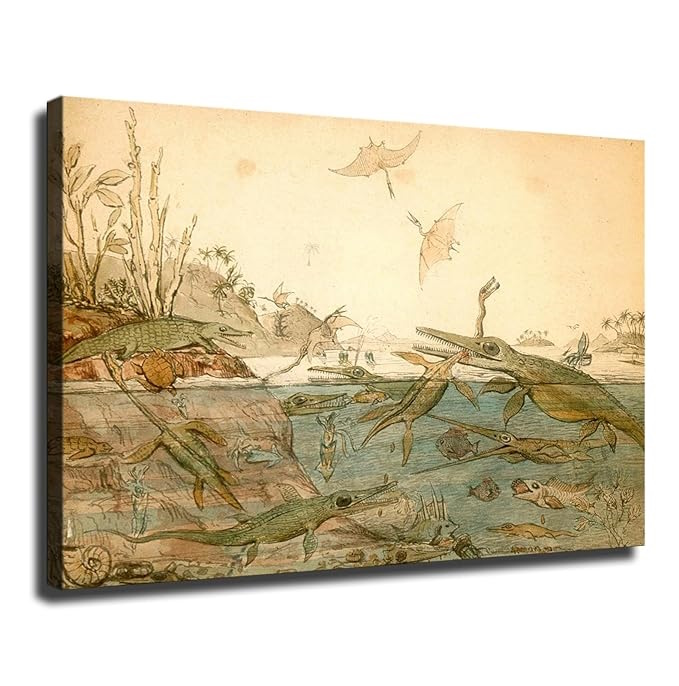

Duria Antiquior (Ancient Dorset) - the first pictorial representation of a scene of prehistoric life based on evidence from fossil reconstructions

Despite her renown in geological circles, in 1830 Anning was having financial difficulties due to hard economic times in Britain, and the long and unpredictable intervals between major fossil finds.

Her rich friends were aware of her situation and tried to help.

In 1820, Colonel Thomas James Birch sold his fossil collection,

mostly purchased from Mary Anning, at auction for the benefit of the Anning family,

after he seen them, during his vist at Lyme Regis, saling their furniture to get

some money to survive.

Aware of her financial problem, and that she was too proud to ask for help, William Buckland and Henry De la Beche cane up with idea to raise a money for her, and to pay tribute for her discoveries.

De la Beche created watercolour drawing, inspired by Buckland's description of the life in the Lias of lyme in the distant past, based on fossils discovered by Mary Anning. He called it "Duria Antiquior" in latine or "A more Ancient Dorset" in English. The drawing, was the first pictorial representation of a scene of prehistoric life based on evidence from fossil reconstructions, a genre now known as paleoart. Paleoart has since become key to the public understanding of - and fascination with - palaeontology.

De la Beche hired the professional artist Georg Scharf, who had earlier done lithographs of Conybeare's sketches of plesiosaur and ichthyosaur skeletons, produce lithographic prints based on the painting. The print was used for educational purposes and widely circulated in scientific circles; it influenced several other such depictions that began to appear in scientific and popular literature. (Several later versions were produced.)

He then sold copies of the print to friends and colleagues at the price of £2 10s (equivalent to £290-£300 today) each and donated the proceeds to Anning.

|

|

| "Duria Antiquior" – "A more Ancient Dorset" watercolour and lithographic print. Images credit: Wikipedia | |

The print run is uncertain but the publisher, Hullmandel, frequently produced very small runs of lithographs on commission. William Buckland played an active role in the distribution of copies: he arranged for copies to be sold to fellows of the Geological Society; he send 100 copies to Mary Anning for her to sell from her shop; and he made use of it in his own lectures in Oxford.

Many of the creatures are depicted in violent interaction. The central figures are a large ichthyosaur biting into the long neck of a plesiosaur. Another plesiosaur is seen trying to surprise a crocodile on the shore, and yet another is using its long neck to seize a pterosaur flying above the water. This emphasis on violent interactions in nature was typical of the Regency era.

De la Beche translated Conybeare's verbal description of marine reptiles into pictorial form, he also painted three different or four different species of ichthyosaurs, reflecting De la Beche and Conybeare work on these animals a decade earlier.

The ichthyosaurs are even shown producing faeces which is gently sinking to the seabed, becoming the coprolites identified by Anning and Buckland.

In addition to the vertebrates there were several invertebrates shown including belemnites depicted as squid-like and an ammonite represented as a floating creature along the lines of a paper nautilus.

|

| Battle of ichthyosaur and plesiosaur as described in Journey to the Center of the Earth book of Jules Verne, on stamp of France 2005. MiNr.: 3943, Scott: 3121. |

Prior to Duria Antiquior Georges Cuvier had published drawings of what he believed certain prehistoric creatures would have looked like in life. Conybeare had drawn a famous cartoon of Buckland sticking his head into a den of prehistoric hyaenas in honour of his well-known analysis of the excavation at Kirkdale Cave, but Duria Antiquior was the first depiction of a scene from deep time showing a variety of prehistoric creatures interacting with one another and their environment based on fossil evidence.

Although an ichthyosaur and plesiosaur would have likely never battled, this widely shared lithograph by artist, geologist and paleontologist Henry De la Beche even inspired author Jules Verne to pen a similar scene in his book, "Journey to the Center of the Earth".The cultural impact of Duria Antiquior was big, it was distributed, copied and plagiarised widely. It and similar reconstructions became a common feature of popular books on fossils through the XIX century.

The biggest part of the painting was reproduced by the Royal Mail, as the background image of presentation pack set with a transparent plastic bag to hold the Mini-Sheet on the middle.

|

|

| Duria Antiquior at the Presentation Pack of the Royal Mail | |

|

According to Sotheby's auction who offered one of the survived, hand-coloured lithograph, copies of Duria Antiquior in 2020 (sold for over GBP16.000), only 24 copies are available today of which the vast majority are in institutional collections. Most surviving copies are of the lithograph in its later state and the only known hand-coloured copy of Duria Antiquior outside the Buckland family collection is in the archives of the British Geological Survey.

The modern reprint of Duria Antiquior can be purchased for few dozen of Euro/US-Dollars on Amazon (USA-1, USA-2, UK-1, UK-2, DE-1, DE-2), or other art dealers as a poster or framed image for living room or an office.

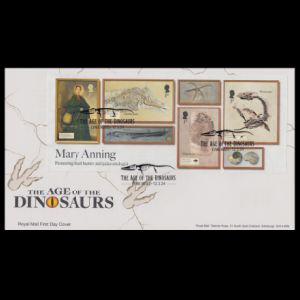

Notes: [1] The label on the Ammonit depicted on selvages of the Mini-Sheet, misspell the species name.

The species name on the label is Ammonites greenoughii, it should be Ammonites greenoughi (with only one "i" letter at the end).

Ammonites greenoughi was named by James de Carle Sowerby in 1816, then described in his "Mineral Conchology of Great Britain" book in 1817 on pages 71-72, the drawing of ammonite is shown on page 70.

Due to the fact, Ammonites greenoughi was described by Sowerby without to mention where and in what strata the specimens was collected, this species was reassigned to to another genus and renamed.

|

|

The sequence of Ammonites greenoughi rename. Image credit: NHM UK (the record/specimen number: PI C 17640) |

"On Schlotheimia greenoughi", by L. F. Spath, published in Geological Magazine, Nr, III, March 1915, p. 100:

Since neither of the large specimens [Ammonites greenoughi] therefore agrees with the lectotype, it seems advisable to refer to these forms only as "Schlotheimia spp. ex aff. Greenoughi (Sowerby)", until duplicate specimens enable us to study their inner whorls and to define their (possibly specific) differences from the lectotype more definitely.

Later on, Schlotheimia greenoughi was moved to Charmasseiceras genus and the species was named Charmasseiceras greenoughi.However, there are some, relative recent documents which erroneously assigned Ammonites greenoughi to another species.

|

|

- I am grateful to Mr. Rob Webley, Editor of Proceedings and Mr. David Bromwich, honorary Librarian of Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society and South West Heritage Trust for their help reading the blurry label on the Ammonite photo, depicted on the Mini-Sheet of the Royal Mail.

- I am grateful to Dr. Jaap Klein from Naturalis Biodiversity Center, in the Netherlands and Dr. Guenter Schweigert from the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, in Germany for their assistance provided during my research of the renaming of the ammonite species.

- I would also like to thank to many individuals from various facebook groups, especially to Dr. Peter Voice, Jeffey Bond, Paul Davis and Paddy Howe for their help and very useful comments.

Products and associated philatelic items

| FDC of Royal Mail | ||

|

|

|

| The same cover, but different postmarks: Ammonite and Mososaurus are of Lyme Regis and dinosaur footprints from Edinburgh. | ||

| First-Day-of-Issue Postmarks (Lyme Regie and Edinburgh) | ||

|

|

|

| Customized FDC | |||

|

|

|

|

| Regular letters sent on the day of the stamps issue, cancelled with commemorative postmarks. To protect these covers from any damage the Royal Mail sent them in plastic bags. The track of the mail sorting machine and marks made by the postman, which could be proof these letters went through the post left on the plastic bag. | |||

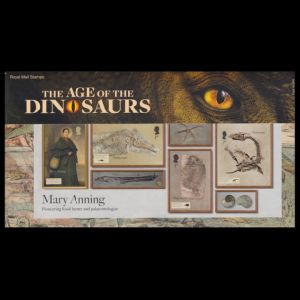

| Stamp Sheets | Mini-Sheet from the uncut Sheet | Presentation Pack |

|

|

|

| A limited edition Press Sheet featuring 12 Mary Anning Miniature Sheets. | A fact-packed foldout souvenir containing stamps, images and insights into Mary Anning and her fossils. |

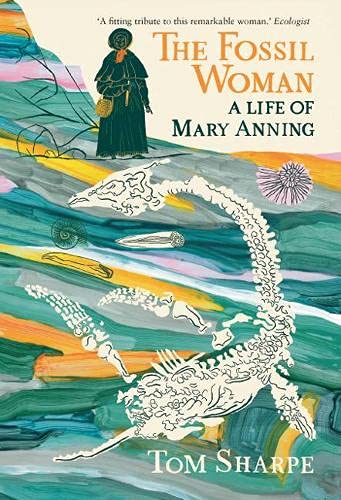

Some Books about Mary Anning

|

|

|

|

|

"The Fossil Woman: A Life of Mary Anning" Amazon: USA, UK, DE. |

"The Dinosaur Hunters: A True Story of Scientific Rivalry and the Discovery of the Prehistoric World" Amazon: USA, UK, DE. |

"Jurassic Mary: Mary Anning and the Primeval Monsters" Amazon: USA, UK, DE. |

"She Sells Seashells. The curious Mary Anning re-imagined" Amazon: USA UK DE |

References:

|

- Technical details and short press releases:

- Stamp Design: "Tha Chase" design agency

-

Mary Anning:

-

One of the major sources about Mary Anning life, used to write this article was the book -

"The Fossil Woman: A Life of Mary Anning"

(Amazon:

USA,

UK,

DE)

and the article

"Mary Anning (1799-1847) of Lyme; the greatest fossilist the world ever knew", by HUGH TORRENS. The British Journal for the History of Science, Sep., 1995, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Sep., 1995), pp. 257-284. - Other articles about Life of Mary Anning: NHM UK, Encyclopedia Britannica, Fossil Guy, BBC, Strange Science, Wikipedia, Fossil and other Living Things, Regency History, Letters from Gondwana.

- The Banknote competition: Bridport News, Change checker, change.org.

- The Statue: Natgeokids, ART UK, NHM UK,

- The Portraits: Wikipedia, Museum Wales, Lyme Regis Mmuseum, Gsl Picture Library, NHM UK,

-

One of the major sources about Mary Anning life, used to write this article was the book -

"The Fossil Woman: A Life of Mary Anning"

(Amazon:

USA,

UK,

DE)

- Dorset: "UNESCO: Visions of the Prehistoric Past", by Zoë Lescaze and Walton Ford. Published in 2017

-

Coprolites:

Wikipedia,

Blog Biodiversity Library.

- Ambroise Pare: Wikipedia.

- Ichthyosaurus: Wikipedia, Oxford University Museum Natural History, Geological Society of London.

-

Plesiosaurus:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Plesiosauria.com,

Gsl Picture Library.

- Plesiosaur: Wikipedia,

- Dapedium (fish): Wikipedia, Weirdn Wild Creatures, More than a Dodo.

- Dimorphodon: Wikipedia, Oxford University Museum Natural History, Weirdn Wild Creatures, Geological Society of London. Lyme Regis Museum,

- bittle_star: Wikipedia, Marine species,

-

The Ammonite:

- Ammonites greenoughi: The fossil forum, Wikisource,

- Plesiospitidiscus ligatus: Ammonites.org, Ammoniten.org,

"Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past", by Zoë Lescaze and Walton Ford. Published in 2017

Amazon: USA UK, DE

Wikipedia, Sothebys, Smithsonian,

-

How much 2GBP in 1830 worth today?

CPI Inflation Calculation,

- William Buckland: Wikipedia, Oxford University Museum of Natural History,

- Henry De la Beche: Wikipedia

- William Daniel Conybeare: Wikipedia

- Gideon Mantell: Wikipedia

- Richard Owen: Wikipedia

- James Sowerby: Wikipedia

- George Greenough: Wikipedia, lindahall, Geological Society of London, Wikipeblogs.ucl.ac.ukdia,

- William Smith: Wikipedia

- Sir Philip Grey Egerton: Wikipedia

- Colonel Thomas James Birch: National Library of New Zealand

- Georges Cuvier: Wikipedia

- Sir Roderick Impey Murchison: The Geological Society of London The Edinburgh Geological Society Linda Hall Library Wikipedia Encyclopedia Britannica

- Charlotte Murchison: Wikipedia

Acknowledgements:

- Many thanks to Mr. Richard Scholey from "The Chase" agency for his explanation about these stamps design process of the agency.

| <prev | back to index | next> |